Andalusia (UK: /ˌændəˈluːsiə, -ziə/, US: /-ʒ(i)ə, -ʃ(i)ə/;[3][4][5] Spanish: Andalucía Spanish pronunciation: [andaluˈθi.a]) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality".[6] The territory is divided into eight provinces: Almería, Cádiz, Córdoba, Granada, Huelva, Jaén, Málaga, and Seville. Its capital city is Seville. The seat of the High Court of Justice of Andalusia is located in the city of Granada.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andalusia

Hispan, Espan, Hispalo or Hispano, is a mythological character of Antiquity, who would derive the name Hispania, according to some ancient writers. Therefore, Hispan is the eponymous hero of Hispania. Hispan is mentioned first by the Gallo-Roman historian Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus (1st century BC) in his work Historiae Philippicae, preserved only in a later summary, probably made in the 3rd century AD by Justinus. During the Middle Ages, Hispan was also known as Espan, told of him various legends.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hispan

The term Hispanic (Spanish: hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.[1][2]

The term commonly applies to Spaniards and Spanish-speaking (Hispanophone) populations and countries in Hispanic America and Hispanic Africa (Equatorial Guinea and the disputed territory of Western Sahara), which were formerly part of the Spanish Empire due to colonization. The cultures of Hispanophone countries outside Spain have been influenced as well by the local pre-Hispanic cultures or other foreign influences. There was also Spanish influence in the former Spanish East Indies, including the Philippines, Marianas, and other nations. However, Spanish is not a predominant language in these regions and, as a result, their inhabitants are not usually considered Hispanic.

Hispanic culture is a set of customs, traditions, beliefs, and art forms in music, literature, dress, architecture, cuisine, and other cultural fields that are generally shared by peoples in Hispanic regions, but which can vary considerably from one country or territory to another. The Spanish language is the main cultural element shared by Hispanic peoples.[3][4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hispanic

Spaniards,[a] or Spanish people, are an ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history, including a number of different languages, both indigenous and local linguistic descendants of the Roman-imposed Latin language, of which Spanish is the largest and the only one that is official throughout the whole country.

Commonly spoken regional languages include, most notably, the sole surviving indigenous language of Iberia, Basque, as well as other Latin-descended Romance languages like Spanish itself, Catalan and Galician. Many populations outside Spain have ancestors who emigrated from Spain and share elements of a Hispanic culture. The most notable of these comprise Hispanic America in the Western Hemisphere.

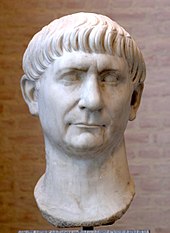

The Roman Republic conquered Iberia during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. Hispania, the name given to Iberia by the Romans as a province of their Empire, became highly acculturated through a process of linguistic and cultural Romanization, and as such, the majority of local languages in Spain today, with the exception of Basque, evolved out of Vulgar Latin which was introduced by Roman soldiers. The Romans laid the foundations for modern Spanish culture and identity, and Spain was the birthplace of important Roman emperors such as Trajan, Hadrian or Theodosius I.

At the end of the Western Roman Empire, the Germanic tribal confederations migrated from Central Europe, invaded the Iberian peninsula and established relatively independent realms in its western provinces, including the Suebi, Alans and Vandals. Eventually, the Visigoths would forcibly integrate all remaining independent territories in the peninsula, including the Byzantine province of Spania, into the Visigothic Kingdom, which more or less unified politically, ecclesiastically, and legally all the former Roman provinces or successor kingdoms of what was then documented as Hispania.

In the early eighth century, the Visigothic Kingdom was conquered by the Umayyad Islamic Caliphate, that arrived to the peninsula in the year 711. The Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula (al-Andalus) soon became autonomous from Baghdad. The handful of small Christian pockets in the north left out of Muslim rule, along the presence of the Carolingian Empire near the Pyrenean range, would eventually lead to the emergence of the Christian kingdoms of León, Castile, Aragon, Portugal and Navarre. Along seven centuries, an intermittent southwards expansion of the latter kingdoms (metahistorically dubbed as a reconquest: the Reconquista) took place, culminating with the Christian seizure of the last Muslim polity (the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada) in 1492, the same year Christopher Columbus arrived in the New World. During the centuries after the Reconquista, the Christian kings of Spain persecuted and expelled ethnic and religious minorities such as Jews and Muslims through the Spanish Inquisition.[29]

A process of political conglomeration among the Christian kingdoms also ensued, and the late 15th-century saw the dynastic union of Castile and Aragon under the Catholic Monarchs, sometimes considered as the point of emergence of Spain as a unified country. The Conquest of Navarre occurred in 1512. There was also a period called Iberian Union, the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Portugal and the Spanish Crown; during which, both countries were ruled by the Spanish Habsburg kings between 1580 and 1640.

In the early modern period, Spain had one of the largest empires in history, which was also one of the first global empires, leaving a large cultural and linguistic legacy that includes over 570 million Hispanophones,[30] making Spanish the world's second-most spoken native language, after Mandarin Chinese. During the Golden Age there were also many advancements in the arts, with the rise of renowned painters such as Diego Velázquez. The most famous Spanish literary work, Don Quixote, was also published during the Golden Age.

The population of Spain has become more diverse due to immigration of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. From 2000 to 2010, Spain had among the highest per capita immigration rates in the world and the second-highest absolute net migration in the world (after the United States).[31] The diverse regional and cultural populations mainly include the Castilians, Catalans, Andalusians, Valencians, Balearics, Canarians, Basques and the Galicians among others.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spaniards

Early populations

The earliest modern humans inhabiting the region of Spain are believed to have been Paleolithic peoples, who may have arrived in the Iberian Peninsula as early as 35,000–40,000 years ago. The Iberians are believed to have arrived or emerged in the region as a culture between the 4th millennium BC and the 3rd millennium BC, settling initially along the Mediterranean coast.[citation needed]

Then Celts settled in Spain during the Iron Age. Some of those tribes in North-central Spain, who had cultural contact with the Iberians, are called Celtiberians. In addition, a group known as the Tartessians and later Turdetanians inhabited southwestern Spain. They are believed to have developed a separate culture influenced by Phoenicia. The seafaring Phoenicians,[32] Greeks, and Carthaginians successively settled trading colonies along the Mediterranean coast over a period of several centuries. Interaction took place with Indigenous peoples. The Second Punic War between the Carthaginians and Romans was fought mainly in what is now Spain and Portugal.[33]

The Roman Republic conquered Iberia during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, and established a series of Latin-speaking provinces in the region. As a result of Roman colonization, the majority of local languages, with the exception of Basque, stem from the Vulgar Latin that was spoken in Hispania (Roman Iberia). A new group of Romance languages of the Iberian Peninsula including Spanish, which eventually became the main language in Spain evolved from Roman expansion. Hispania emerged as an important part of the Roman Empire and produced notable historical figures such as Trajan, Hadrian, Seneca and Quintilian.

The Germanic Vandals and Suebi, with Iranian Alans under King Respendial, arrived in the peninsula in 409 AD. Part of the Vandals with the remaining Alans, now under Geiseric, removed to North Africa after a few conflicts with another Germanic tribe, the Visigoths. The latter were established in Toulouse and supported Roman campaigns against the Vandals and Alans in 415–19 AD.

The Visigoths became the dominant power in Iberia and reigned for three centuries. They were highly romanized in the eastern Empire and already Christians, so they became fully integrated into the late Iberian-Roman culture.

The Suebi were another Germanic tribe in the west of the peninsula; some sources said that they became established as federates of the Roman Empire in the old Northwestern Roman province of Gallaecia (roughly, present-day northern Portugal and Galicia). But they were largely independent and raided neighboring provinces to expand their political control over ever-larger portions of the southwest after the Vandals and Alans left. They created a totally independent Suebic Kingdom. In 447 AC they converted to Roman Catholicism under King Rechila.

After being checked and reduced in 456 AD by the Visigoths, the Suebic Kingdom survived to 585 AD. It was decimated as an independent political unit by the Visigoths, after having been involved in the internal affairs of their kingdom.

Middle Ages

After two centuries of domination by the Visigothic Kingdom, the Iberian Peninsula was invaded by a Muslim force under Tariq Bin Ziyad in 711. This army consisted mainly of ethnic Berbers from the Ghomara tribe, who were reinforced by Arabs from Syria once the conquest was complete. Only a remote mountainous area in the far north retained independence, eventually developing as the Christian Kingdom of Asturias.

Muslim Iberia became part of the Umayyad Caliphate and would be known as Al-Andalus. The Berbers of Al Andalus revolted as early as 740 AD, halting Arab expansion across the Pyrenee Mountains into France. Upon the collapse of the Umayyad in Damascus, Spain was seized by Yusuf al Fihri. The exiled Umayyad Prince Abd al-Rahman I next seized power, establishing himself as Emir of Cordoba. Abd al Rahman III, his grandson, proclaimed a Caliphate in 929, marking the beginning of the Golden Age of Al Andalus. This policy was the effective power of the peninsula and Western North Africa; it competed with the Shiite rulers of Tunis and frequently raided the small Christian kingdoms in the North.

The Caliphate of Córdoba effectively collapsed during a ruinous civil war between 1009 and 1013; it was not finally abolished until 1031, when al-Andalus broke up into a number of mostly independent mini-states and principalities called taifas. These were generally too weak to defend themselves against repeated raids and demands for tribute from the Christian states to the north and west, which were known to the Muslims as "the Galician nations". These had expanded from their initial strongholds in Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque country, and the Carolingian Marca Hispanica to become the Kingdoms of Navarre, León, Portugal, Castile and Aragon, and the County of Barcelona. Eventually they began to conquer territory, and the Taifa kings asked for help from the Almoravids, Muslim Berber rulers of the Maghreb. But the Almoravids went on to conquer and annex all the Taifa kingdoms.

In 1086 the Almoravid ruler of Morocco, Yusuf ibn Tashfin, was invited by the Muslim princes in Iberia to defend them against Alfonso VI, King of Castile and León. In that year, Tashfin crossed the straits to Algeciras and inflicted defeat on the Christian army at the Battle of Sagrajas. By 1094, Yusuf ibn Tashfin had removed all Muslim princes in Iberia and had annexed their states, except for the one at Zaragoza. He also regained Valencia from the Christians. About this time a massive process of conversion to Islam took place, and Muslims comprised the majority of the population in Spain by the end of the 11th century.

The Almoravids were succeeded by the Almohads, another Berber dynasty, after the victory of Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur over the Castilian Alfonso VIII at the Battle of Alarcos in 1195. In 1212 a coalition of Christian kings under the leadership of the Castilian Alfonso VIII defeated the Almohads at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa. But the Almohads continued to rule Al-Andalus for another decade, though with much reduced power and prestige. The civil wars following the death of Abu Ya'qub Yusuf II rapidly led to the re-establishment of taifas. The taifas, newly independent but weakened, were quickly conquered by the kingdoms of Portugal, Castile, and Aragon. After the fall of Murcia (1243) and the Algarve (1249), only the Emirate of Granada survived as a Muslim state, tributary of Castile until 1492.

In 1469 the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile signaled a joining of forces to attack and conquer the Emirate of Granada. The King and Queen convinced the Pope to declare their war a crusade. The Christians were successful and finally, in January 1492, after a long siege, the Moorish sultan Muhammad XII surrendered the fortress palace, the renowned Alhambra.

Spain conquered the Canary Islands between 1402 and 1496. Their indigenous Berber population, the Guanches, were gradually absorbed by intermarrying with Spanish settlers.

Spanish conquest of the Iberian part of Navarre was begun by Ferdinand II of Aragon and completed by Charles V. The series of military campaigns extended from 1512 to 1524, while the war lasted until 1528 in the Navarre to the north of the Pyrenees. Between 1568 and 1571, Charles V armies fought and defeated a general insurrection of the Muslims of the mountains of Granada. Charles V then ordered the expulsion of up to 80,000 Granadans from the province and their dispersal throughout Spain.

The union of the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon as well as the conquest of Granada, Navarre and the Canary Islands led to the formation of the Spanish state as known today. This allowed for the development of a Spanish identity based on the Spanish language and a local form of Catholicism. This gradually developed in a territory that remained culturally, linguistically and religiously very diverse.

A majority of Jews were forcibly converted to Catholicism during the 14th and 15th centuries and those remaining were expelled from Spain in 1492. The open practice of Islam by Spain's sizeable Mudejar population was similarly outlawed. Furthermore, between 1609 and 1614, a significant number of Moriscos— (Muslims who had been baptized Catholic) were expelled by royal decree.[34] Although initial estimates of the number of Moriscos expelled such as those of Henri Lapeyre reach 300,000 moriscos (or 4% of the total Spanish population), the extent and severity of the expulsion has been increasingly challenged by modern historians. Nevertheless, the eastern region of Valencia, where ethnic tensions were highest, was particularly affected by the expulsion, suffering economic collapse and depopulation of much of its territory.

The Islamic legacy in Spain has been long lasting, and among many others, accounts for two of the eight masterpieces of Islamic architecture from around the world: the Alhambra of Granada and the Cordoba Mosque;[35] the Palmeral of Elche [36] is listed as a World Heritage Site due to its uniqueness.[37]

Those who avoided expulsion or who managed to return to Spain merged into the dominant culture.[38] The last mass prosecution against Moriscos for crypto-Islamic practices took place in Granada in 1727, with most of those convicted receiving relatively light sentences. By the end of the 18th century, Indigenous Islam and Morisco identity were considered to have been extinguished in Spain.[39]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spaniards

Spain

Spain – Spain initially held to formal neutrality, but when Italy entered the war in June 1940, Francisco Franco changed Spain's status to that of "non-belligerent" and proceeded to occupy Tangiers. From June 1940 until February 1941, the Francoist regime was greatly tempted by interventionism; a prominent Germanophile, Foreign Minister Ramón Serrano Suñer was highly influential in the government.[6] However, meetings with German officials, including the Hendaye meeting between Franco and Hitler on 23 October 1940, did not bring formal entry of Spain into the war.

Spain – Spain initially held to formal neutrality, but when Italy entered the war in June 1940, Francisco Franco changed Spain's status to that of "non-belligerent" and proceeded to occupy Tangiers. From June 1940 until February 1941, the Francoist regime was greatly tempted by interventionism; a prominent Germanophile, Foreign Minister Ramón Serrano Suñer was highly influential in the government.[6] However, meetings with German officials, including the Hendaye meeting between Franco and Hitler on 23 October 1940, did not bring formal entry of Spain into the war.

- Operation Barbarossa shifted the main theater of war away from the Mediterranean, lessening Spain's interest in intervention. The less-relevant Serrano Suñer was still able to create the Blue Division,[7] made up of Spanish volunteers to fight for the Axis. With the conflict decidedly turning in favor of the Allies, Franco returned the status of Spain to one of "vigilant neutrality" on 1 October 1943.[8]

- During most of the war, Spain had been a key provider of strategic tungsten ore to Nazi Germany. Amid heavy Allied diplomatic and economic pressure, Spain signed a secret deal with the United States and United Kingdom on 2 May 1944 to drastically limit tungsten exports to Germany and expel German spies from Spanish soil.[9]

Sweden

Sweden

– Before the war, Sweden and the other Nordic countries announced their

planned neutrality in any large European conflict. When Finland was

invaded by the Soviet Union in the Winter War, Sweden changed its position to that of a non-belligerent,

which was not defined by international treaties, thus freeing Sweden

from the restrictions of neutrality. Among other things, it allowed the

Swedish government to support Finland during the Winter War,

allowed German soldiers on leave to travel through Sweden, and at one

point allowed a combat division to travel from Norway to Finland through

Sweden. The transit of German troops through Finland and Sweden and Swedish iron-ore mining during World War II

helped the German war effort. Sweden had disarmed after World War I and

was in no position to resist German threats militarily by 1940.

Sweden

– Before the war, Sweden and the other Nordic countries announced their

planned neutrality in any large European conflict. When Finland was

invaded by the Soviet Union in the Winter War, Sweden changed its position to that of a non-belligerent,

which was not defined by international treaties, thus freeing Sweden

from the restrictions of neutrality. Among other things, it allowed the

Swedish government to support Finland during the Winter War,

allowed German soldiers on leave to travel through Sweden, and at one

point allowed a combat division to travel from Norway to Finland through

Sweden. The transit of German troops through Finland and Sweden and Swedish iron-ore mining during World War II

helped the German war effort. Sweden had disarmed after World War I and

was in no position to resist German threats militarily by 1940.

- In 1943, the Swedish Armed Forces were much improved, and all such deals with Germany were terminated. Hitler considered invading Sweden, but when Göring protested, Hitler dropped the plan. The Swedish SKF company supplied the majority of ball-bearings used in Germany and was also important to Allied aircraft production.[10]

- Swedish Intelligence cracked the German Geheimschreiber cipher and shared decrypted information with the Allies. Stalin was informed well in advance of Hitler's planned invasion of the Soviet Union but chose not to believe the information.

- Danish resistance worked with Sweden to carry out the 1943 rescue of the Danish Jews by shipping them to Sweden. During the Liberation of Finnmark, Sweden sent Norwegian "police" troops over the border to link up with Allied forces. At the end of the war, Sweden was preparing to join the Allied invasion of Norway and Denmark if the occupying Wehrmacht forces rejected a general armistice.

Switzerland

Switzerland

– As in World War I, Switzerland maintained its historic neutrality. It

depended on German coal, with 10 million tons imported during the war,

comprising 41% of Swiss energy supplies. The Swiss military often opened

fire on Axis bombers invading its airspace;

Switzerland also shot down Allied planes over its territory on several

occasions. Throughout the war, cities in Switzerland were accidentally bombed by both Axis and Allied aircraft. The Axis did have plans for an invasion of Switzerland, but Switzerland had formed complex fortifications

and amassed thousands of soldiers in the mountains to thwart any Axis

invasion. Perhaps for these reasons and the extreme mountainous

conditions in Switzerland the invasion plans were never realised.Perhaps for these reasons and the extreme mountainous conditions in Switzerland the invasion plans were never realised.[speculation?]

Switzerland

– As in World War I, Switzerland maintained its historic neutrality. It

depended on German coal, with 10 million tons imported during the war,

comprising 41% of Swiss energy supplies. The Swiss military often opened

fire on Axis bombers invading its airspace;

Switzerland also shot down Allied planes over its territory on several

occasions. Throughout the war, cities in Switzerland were accidentally bombed by both Axis and Allied aircraft. The Axis did have plans for an invasion of Switzerland, but Switzerland had formed complex fortifications

and amassed thousands of soldiers in the mountains to thwart any Axis

invasion. Perhaps for these reasons and the extreme mountainous

conditions in Switzerland the invasion plans were never realised.Perhaps for these reasons and the extreme mountainous conditions in Switzerland the invasion plans were never realised.[speculation?]

Turkey

Turkey

was neutral until several months before the end of the war, at which

point it joined the Allies. Prior to the outbreak of war, Turkey signed a

Mutual Aid Pact with France and Britain in 1939. After the German invasion of France,

however, Turkey remained neutral, relying on a clause excusing them if

military action might bring conflict with the USSR. In June 1941, after

neighbouring Bulgaria joined the Axis and allowed Germany to move troops

through to invade Yugoslavia and Greece, Turkey signed a treaty of friendship with Germany. Winston Churchill and his military staff met the Turkish president on 30 January 1943 in the Adana Conference, although Turkey did not then change its position.

Turkey

was neutral until several months before the end of the war, at which

point it joined the Allies. Prior to the outbreak of war, Turkey signed a

Mutual Aid Pact with France and Britain in 1939. After the German invasion of France,

however, Turkey remained neutral, relying on a clause excusing them if

military action might bring conflict with the USSR. In June 1941, after

neighbouring Bulgaria joined the Axis and allowed Germany to move troops

through to invade Yugoslavia and Greece, Turkey signed a treaty of friendship with Germany. Winston Churchill and his military staff met the Turkish president on 30 January 1943 in the Adana Conference, although Turkey did not then change its position.- Turkey was an important producer of chromite, a strategic material for metallurgy to which Germany had limited access. The Germans wanted it, and the Allies wanted to prevent them from getting it. So, chromite was the key issue in Turkey's negotiations with both sides. Turkey would backpedal on its agreement to supply Nazi Germany with chromite. After instead selling it to the rival nations the United States and the United Kingdom after the two allied nations agreed to also purchase dried fruit and tobacco from Turkey as well.[11] Turkey halted its sales to Germany in April 1944 and broke off relations in August. In February 1945, after the Allies made its invitation to the inaugural meeting of the United Nations (along with the invitations of several other nations) conditional on full belligerency, Turkey declared war on the Axis powers, but no Turkish troops ever saw combat.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neutral_powers_during_World_War_II#Sweden

The Swiss franc is the currency and legal tender of Switzerland and Liechtenstein. It is also legal tender in the Italian exclave of Campione d'Italia which is surrounded by Swiss territory.[6] The Swiss National Bank (SNB) issues banknotes and the federal mint Swissmint issues coins.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swiss_franc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franken

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bavaria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fief

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franconia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_France

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peasant

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neander

A fief (/fiːf/; Latin: feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal allegiance, services, and/or payments. The fees were often lands, land revenue or revenue-producing real property like a watermill, held in feudal land tenure: these are typically known as fiefs or fiefdoms.[1] However, not only land but anything of value could be held in fee, including governmental office, rights of exploitation such as hunting, fishing or felling trees, monopolies in trade, money rents and tax farms.[1] There never existed a standard feudal system, nor did there exist only one type of fief. Over the ages, depending on the region, there was a broad variety of customs using the same basic legal principles in many variations.[2][3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fief

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed during the Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages in Europe and lasted in some countries until the mid-19th century.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serfdom

In Eastern Europe, the institution persisted until the mid-19th century. In the Austrian Empire, serfdom was abolished by the 1781 Serfdom Patent; corvées continued to exist until 1848. Serfdom was abolished in Russia in 1861.[3] Prussia declared serfdom unacceptable in its General State Laws for the Prussian States in 1792 and finally abolished it in October 1807, in the wake of the Prussian Reform Movement.[4] In Finland, Norway, and Sweden, feudalism was never fully established, and serfdom did not exist; in Denmark, serfdom-like institutions did exist in both stavns (the stavnsbånd, from 1733 to 1788) and its vassal Iceland (the more restrictive vistarband, from 1490 until 1894).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serfdom

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague)[a] was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causing the deaths of 75–200 million people,[1] peaking in Europe from 1347 to 1351.[2][3] Bubonic plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis spread by fleas, but during the Black Death it probably also took a secondary form, spread by person-to-person contact via aerosols, causing pneumonic plague.[4][5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Death

In Europe, the Iron Age is the last stage of the prehistoric period and the first of the protohistoric periods,[1] which initially meant descriptions of a particular area by Greek and Roman writers. For much of Europe, the period came to an abrupt end after conquest by the Romans, though ironworking remained the dominant technology until recent times. Elsewhere, the period lasted until the early centuries AD, and either Christianization or a new conquest in the Migration Period.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iron_Age_Europe

Inferno (Italian: [iɱˈfɛrno]; Italian for "Hell") is the first part of Italian writer Dante Alighieri's 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy. It is followed by Purgatorio and Paradiso. The Inferno describes Dante's journey through Hell, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil. In the poem, Hell is depicted as nine concentric circles of torment located within the Earth; it is the "realm ... of those who have rejected spiritual values by yielding to bestial appetites or violence, or by perverting their human intellect to fraud or malice against their fellowmen".[1] As an allegory, the Divine Comedy represents the journey of the soul toward God, with the Inferno describing the recognition and rejection of sin.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inferno_(Dante)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_the_Great

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_conquest_of_Siberia

The Russian conquest of Siberia took place during 1580–1778, when the Khanate of Sibir became a loose political structure of vassalages that were being undermined by the activities of Russian explorers. Although outnumbered, the Russians pressured the various family-based tribes into changing their loyalties and establishing distant forts from which they conducted raids. It is traditionally considered that Yermak Timofeyevich's campaign against the Siberian Khanate began in 1580. The annexation of Siberia and the Far East to Russia was resisted by local residents and took place against the backdrop of fierce battles between the indigenous peoples and the Russian Cossacks, who often committed atrocities against the indigenous peoples.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_conquest_of_Siberia

No comments:

Post a Comment