Indivisible may refer to:

Mathematics

- Method of indivisibles, the historical name of what is now known as Cavalieri's principle

- Absence of divisibility (ring theory)

Arts

Films

- Indivisible (2016 film), a 2016 Italian film

- Indivisible (2018 film), a 2018 American film

Music

- Indivisible, album by Lungfish (band) 1997

- "Indivisible", song by Marie-Mai

- "Indivisible", song by Pillar from Fireproof (Pillar album)

- "Indivisible", song by Hatebreed

- "Indivisible", song by Lungfish (band)

- "Indivisible", song by The Dirtbombs

- "Indivisible", song by Plankeye

- "Indivisible", song by Crüxshadows

- "Indivisible", song by Betty Wright

- "Indivisible", song by Yellowjackets

Other media

- Indivisible, a novel by Fanny Howe (2003)

- Indivisible (video game)

Other uses

- French ship Indivisible (1799)

- Indivisible movement, a progressive movement initiated as a reaction to the election of Donald Trump as US President in 2016

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indivisible

ot to be confused with Cavalieri's quadrature formula.

In geometry, Cavalieri's principle, a modern implementation of the method of indivisibles, named after Bonaventura Cavalieri, is as follows:[1]

- 2-dimensional case: Suppose two regions in a plane are included between two parallel lines in that plane. If every line parallel to these two lines intersects both regions in line segments of equal length, then the two regions have equal areas.

- 3-dimensional case: Suppose two regions in three-space (solids) are included between two parallel planes. If every plane parallel to these two planes intersects both regions in cross-sections of equal area, then the two regions have equal volumes.

Today Cavalieri's principle is seen as an early step towards integral calculus, and while it is used in some forms, such as its generalization in Fubini's theorem and layer cake representation, results using Cavalieri's principle can often be shown more directly via integration. In the other direction, Cavalieri's principle grew out of the ancient Greek method of exhaustion, which used limits but did not use infinitesimals.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cavalieri%27s_principle

In mathematics, the notion of a divisor originally arose within the context of arithmetic of whole numbers. With the development of abstract rings, of which the integers are the archetype, the original notion of divisor found a natural extension.

Divisibility is a useful concept for the analysis of the structure of commutative rings because of its relationship with the ideal structure of such rings.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divisibility_(ring_theory)

In concurrent programming, an operation (or set of operations) is linearizable if it consists of an ordered list of invocation and response events, that may be extended by adding response events such that:

- The extended list can be re-expressed as a sequential history (is serializable).

- That sequential history is a subset of the original unextended list.

Informally, this means that the unmodified list of events is linearizable if and only if its invocations were serializable, but some of the responses of the serial schedule have yet to return.[1]

In a concurrent system, processes can access a shared object at the same time. Because multiple processes are accessing a single object, there may arise a situation in which while one process is accessing the object, another process changes its contents. Making a system linearizable is one solution to this problem. In a linearizable system, although operations overlap on a shared object, each operation appears to take place instantaneously. Linearizability is a strong correctness condition, which constrains what outputs are possible when an object is accessed by multiple processes concurrently. It is a safety property which ensures that operations do not complete in an unexpected or unpredictable manner. If a system is linearizable it allows a programmer to reason about the system.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linearizability

In computer science, a consistency model specifies a contract between the programmer and a system, wherein the system guarantees that if the programmer follows the rules for operations on memory, memory will be consistent and the results of reading, writing, or updating memory will be predictable. Consistency models are used in distributed systems like distributed shared memory systems or distributed data stores (such as filesystems, databases, optimistic replication systems or web caching). Consistency is different from coherence, which occurs in systems that are cached or cache-less, and is consistency of data with respect to all processors. Coherence deals with maintaining a global order in which writes to a single location or single variable are seen by all processors. Consistency deals with the ordering of operations to multiple locations with respect to all processors.

High level languages, such as C++ and Java, maintain the consistency contract by translating memory operations into low-level operations in a way that preserves memory semantics, reordering some memory instructions, and encapsulating required synchronization with library calls such as pthread_mutex_lock().[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consistency_model

In computer science, distributed shared memory (DSM) is a form of memory architecture where physically separated memories can be addressed as a single shared address space. The term "shared" does not mean that there is a single centralized memory, but that the address space is shared—i.e., the same physical address on two processors refers to the same location in memory.[1]: 201 Distributed global address space (DGAS), is a similar term for a wide class of software and hardware implementations, in which each node of a cluster has access to shared memory in addition to each node's private (i.e., not shared) memory.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_shared_memory

In computer science, shared memory is memory that may be simultaneously accessed by multiple programs with an intent to provide communication among them or avoid redundant copies. Shared memory is an efficient means of passing data between programs. Depending on context, programs may run on a single processor or on multiple separate processors.

Using memory for communication inside a single program, e.g. among its multiple threads, is also referred to as shared memory.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shared_memory

Overlapping instructions

On processor architectures with variable-length instruction sets[5] (such as Intel's x86 processor family) it is, within the limits of the control-flow resynchronizing phenomenon known as the Kruskal Count,[6][5] sometimes possible through opcode-level programming to deliberately arrange the resulting code so that two code paths share a common fragment of opcode sequences. These are called overlapping instructions, overlapping opcodes, overlapping code, overlapped code, instruction scission, or jump into the middle of an instruction, and represent a form of superposition.[7][8][9]

In the 1970s and 1980s, overlapping instructions were sometimes used to preserve memory space. One example were in the implementation of error tables in Microsoft's Altair BASIC, where interleaved instructions mutually shared their instruction bytes.[10][5][7] The technique is rarely used today, but might still be necessary to resort to in areas where extreme optimization for size is necessary on byte-level such as in the implementation of boot loaders which have to fit into boot sectors.[nb 2]

It is also sometimes used as a code obfuscation technique as a measure against disassembly and tampering.[5]

The principle is also utilized in shared code sequences of fat binaries which must run on multiple instruction-set-incompatible processor platforms.

This property is also used to find unintended instructions called gadgets in existing code repositories and is utilized in return-oriented programming as alternative to code injection for exploits such as return-to-libc attacks.[11][5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Machine_code#Overlapping_instructions

In computer architecture, cache coherence is the uniformity of shared resource data that ends up stored in multiple local caches. When clients in a system maintain caches of a common memory resource, problems may arise with incoherent data, which is particularly the case with CPUs in a multiprocessing system.

In the illustration on the right, consider both the clients have a cached copy of a particular memory block from a previous read. Suppose the client on the bottom updates/changes that memory block, the client on the top could be left with an invalid cache of memory without any notification of the change. Cache coherence is intended to manage such conflicts by maintaining a coherent view of the data values in multiple caches.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cache_coherence

Indivisible security or the indivisibility of security is a term first used during the Cold War.[1][2] First included in the Helsinki Accords as the "indivisibility of security in Europe", the term states that the security of one nation is inseparable from other countries in its region.[1] In 2022, Russia has used this term to justify its military build-up near Ukraine, which ultimately led to a full-fledged invasion.[1] The term has also been promoted by China,[3] including as part of its promoted "global security initiative".[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indivisible_security

The uncertainty reduction theory, also known as initial interaction theory, developed in 1975 by Charles Berger and Richard Calabrese, is a communication theory from the post-positivist tradition. It is one of the few communication theories that specifically looks into the initial interaction between people prior to the actual communication process. The theory asserts the notion that, when interacting, people need information about the other party in order to reduce their uncertainty. In gaining this information people are able to predict the other's behavior and resulting actions, all of which according to the theory is crucial in the development of any relationship.[1][2]

Berger and Calabrese explain the connection between their central concept of uncertainty and seven key variables of relationship development with a series of axioms, and deduce a series of theorems accordingly. Within the theory two types of uncertainty are identified; cognitive uncertainty and behavioral uncertainty. There are three types of strategies which people may use to seek information about someone: passive, active, and interactive. Furthermore, the initial interaction of strangers can be broken down into individual stages—the entry stage, the personal stage, and the exit stage. According to the theory, people find uncertainty in interpersonal relationships unpleasant and are motivated to reduce it through interpersonal communication.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncertainty_reduction_theory

his article is about the societal concept. For the similar concept that relates to individuals, see Ambiguity aversion.

In cross-cultural psychology, uncertainty avoidance is how cultures differ on the amount of tolerance they have of unpredictability.[1] Uncertainty avoidance is one of five key qualities or dimensions measured by the researchers who developed the Hofstede model of cultural dimensions to quantify cultural differences across international lines and better understand why some ideas and business practices work better in some countries than in others. [2] According to Geert Hofstede, "The fundamental issue here is how a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known: Should we try to control it or just let it happen?"[1]

The uncertainty avoidance dimension relates to the degree to which individuals of a specific society are comfortable with uncertainty and the unknown. Countries displaying strong uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) believe and behave in a strict manner. Individuals belonging to those countries also avoid unconventional ways of thinking and behaving. Weak UAI societies display more ease in regards to uncertainty.[2] People in cultures with high uncertainty avoidance try to minimize the occurrence of unknown and unusual circumstances and to proceed with careful changes step by step by planning and by implementing rules, laws and regulations. In contrast, low uncertainty avoidance cultures accept and feel comfortable in unstructured situations or changeable environments and try to have as few rules as possible. People in these cultures tend to be more pragmatic and more tolerant of change.[3]

When it comes to the tolerance of unpredictability, the areas which uncertainty avoidance deals with the most are technology, law, and religion. Technology assists with the uncertainty done by nature with new developments. Law defends the uncertainty of behavior by the people with rules that are set. Religion accepts the uncertainty people cannot get protected from. Individuals use their beliefs to get through their uncertainties.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncertainty_avoidance

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

Australia

- Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

United States

- Grant, Alabama

- Grant, Inyo County, California

- Grant, Colorado

- Grant-Valkaria, Florida

- Grant, Iowa

- Grant, Michigan

- Grant, Minnesota

- Grant, Nebraska

- Grant, Ohio, an unincorporated community

- Grant, Washington

- Grant, Wisconsin (disambiguation) (six towns)

- Grant City, Indiana

- Grant City, Missouri

- Grant City, Staten Island

- Grant Lake (disambiguation), several lakes

- Grant Park, Illinois

- Grant Park (Chicago)

- Grant Town, West Virginia

- Grant Township (disambiguation) (100 townships in 12 states)

- Grant Village in Yellowstone National Park

- Grants, New Mexico

- Grants Pass, Oregon

- U.S. Grant Bridge over Ohio River and Scioto River

- General Grant National Memorial aka Grant's Tomb

India

- Jolly Grant Airport Dehradun, Uttarakhand

Canada

- Rural Municipality of Grant No. 372, Saskatchewan

People

- Grant (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

- Grant (surname), including a list of people and fictional characters

- Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885), the 18th president of the United States and general of the Union during the American Civil War

- Cary Grant (1904–1986), British-American actor

- Hugh Grant (born 1960), British actor

- Richard E. Grant (born 1957), British-Swazi actor

- Justice Grant (disambiguation), judges named Grant

- Clan Grant, a Highland Scottish clan

Art, entertainment, and media

- Grant (book), a 2017 biography of Ulysses S. Grant by Ron Chernow

- Grant (miniseries), a 2020 miniseries based on the Chernow book

- "Grant", a poem by Patti Smith from her 1978 book Babel

Businesses

- Donald M. Grant, Publisher, Inc., a fantasy and science fiction small press publisher in New Hampshire

- W. T. Grant variety store, a chain of mass-merchandise stores

- William Grant & Sons, a Scotch whisky distilling company

Law and philanthropy

- Grant (law), a term in conveyancing

- Grant (money), an award usually funded by a government, business, or foundation, often with not-for-profit preconditions

- Spanish and Mexican land grants in New Mexico

- Spanish land grants in Florida

- Grant v Torstar Corp, a leading Supreme Court of Canada case on responsible communication in the public interest as a defence against defamation

Vehicles and transportation

- Grant (automobile), a defunct Findlay, Ohio auto manufacturer

- M3 Lee, an American tank, a modified version was called the Grant

- USS Grant, several ships of the U.S. Navy

Other uses

- Grant, colloquial term for a United States fifty-dollar bill which bears a portrait of President Ulysses S. Grant

- Cyclone Grant, a tropical cyclone that made landfall near Darwin, Australia, in late-December 2011

- Grant of arms in nobility

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grant

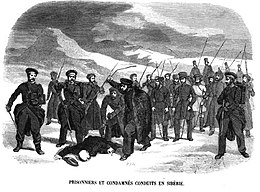

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term expulsion is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation is more used in national (municipal) law.[1] Forced displacement or forced migration of an individual or a group may be caused by deportation, for example ethnic cleansing, and other reasons. A person who has been deported or is under sentence of deportation is called a deportee.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deportation

Forced displacement (also forced migration or forced relocation) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence or human rights violations".[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forced_displacement

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer, it also includes indirect methods aimed at forced migration by coercing the victim group to flee and preventing its return, such as murder, rape, and property destruction.[2][3][4] It constitutes a crime against humanity and may also fall under the Genocide Convention, even as ethnic cleansing has no legal definition under international criminal law.[2][5][6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnic_cleansing

Arbitrary arrest and arbitrary detention are the arrest or detention of an individual in a case in which there is no likelihood or evidence that they committed a crime against legal statute, or in which there has been no proper due process of law or order.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arbitrary_arrest_and_detention

Adjective

incommunicado (not comparable)

In a state or condition of inability or unwillingness to communicate.Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suffer exile, but sometimes social entities like institutions (e.g. the papacy or a government) are forced from their homeland.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exile

A tax exile is a person who leaves a country to avoid the payment of income tax or other taxes. The term refers to an individual who already owes money to the tax authorities or wishes to avoid being liable in the future for taxation at what they consider high tax rates, instead choosing to reside in a foreign country or jurisdiction which has no taxes or lower tax rates.

In general, there is no extradition agreement between countries which covers extradition for outstanding tax liabilities. Going into tax exile is a form of tax mitigation or avoidance. A tax exile normally cannot return to their home country without being subject to outstanding tax liabilities. This may prevent the individual from leaving the country until these taxes owing have been paid.

Most countries tax individuals who are resident in their jurisdiction. Though residency rules vary, most commonly individuals are resident in a country for taxation purposes if they spend at least six months (or some other period) in any one tax year in the country, and/or have an abiding attachment to the country, such as owning a fixed property.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tax_exile

In an extradition, one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, over to the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdictions and depends on the arrangements made between them. In addition to legal aspects of the process, extradition also involves the physical transfer of custody of the person being extradited to the legal authority of the requesting jurisdiction.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extradition

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spain-Var-Rus-As-etc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/bruen-mest-eur-lat-etc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/af-var-etc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Police_misconduct

A mass arrest occurs when police apprehend large numbers of suspects at once. This sometimes occurs at protests. Some mass arrests are also used in an effort to combat gang activity.[1] This is sometimes controversial, and lawsuits sometimes result.[2] In police science, it is deemed to be good practice to plan for the identification of those arrested during mass arrests, since it is unlikely that the officers will remember everyone they arrested.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if allowed at all. House arrest is an alternative to being in a prison while awaiting trial or after sentencing.

While house arrest can be applied to criminal cases when prison does not seem an appropriate measure, the term is often applied to the use of house confinement as a measure of repression by authoritarian governments against political dissidents. In these cases, the person under house arrest often does not have access to any means of communication with people outside of the home; if electronic communication is allowed, conversations may be monitored.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_arrest

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another organization, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertaking such an effort is labeled as purging itself. Purges can be either nonviolent or violent, with the former often resolved by the simple removal of those who have been purged from office, and the latter often resolved by the imprisonment, exile, or murder of those who have been purged.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purge

Unknown or The Unknown may refer to:

Film

- The Unknown (1915 comedy film), a silent boxing film

- The Unknown (1915 drama film)

- The Unknown (1922 drama film)

- The Unknown (1927 film), a silent horror film starring Lon Chaney

- The Unknown (1936 film), a German drama film

- The Unknown (1946 film), a mystery film

- Anjaane: The Unknown, a 2005 Bollywood horror movie

- The Unknown, a 2005 action/thriller starring Miles O'Keeffe

- Unknown (2006 film), a thriller starring James Caviezel

- Unknown (2011 film), a thriller starring Liam Neeson

Literature

- Unknown (magazine), an American pulp fantasy fiction magazine published from 1939 to 1943

- The Unknown (novel), a 1998 book by K. A. Applegate

- The Unknown, a comic book mini-series by Mark Waid

Music

- The Unknown (Madeline Juno album) (2014)

- Unknown (Rasputina album) (2015)

- The Unknown (The Vision Bleak album) (2016)

- The Unknown, a 2014 album by Dillon

- "The Unknown" (song), by 10 Years, 2019

- "The Unknown", a song by Crossfade from Crossfade, 2004

- "The Unknown", a song by Shadows Fall from Fire from the Sky, 2012

- "Unknown", a song by Reks from The Greatest X, 2016

Science and mathematics

- Unknown (mathematics), a variable that appears in an equation for which a solution is sought

- Unknown, the ongoing answer to an open problem

Video games

- Unknown (video game) or Amnesia: The Dark Descent, a 2010 video game

- Unknown (Tekken), a character in Tekken

Other uses

- The Unknown (Over the Garden Wall), an episode of Over the Garden Wall

- The Unknown, a location in Over the Garden Wall

- The Unknown, a sculpture by Kenny Hunter

- Unknown, a Unicode script

- The Unknowns, a self-proclaimed ethical hacking group

People

- Unknown Hinson (born 1954), musician and performer

- The Unknown Comic (born 1945), Canadian actor and comedian

- The Unknown DJ, American disc jockey and record producer

- Unknown T (born 1998), British rapper

See also

- The Great Unknown (disambiguation)

- L'Inconnue de la Seine (died c. 1880), unidentified young woman whose death mask was the model for the CPR doll Resusci Anne

- Unknown known

- Unknown Soldier (disambiguation)

- Unown, a Pokémon species

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unknown

Xenophobia (from Ancient Greek ξένος (xénos) 'strange, foreign, alien', and φόβος (phóbos) 'fear')[1] is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange.[2][3][4] It is an expression which is based on the perception that a conflict exists between an in-group and an out-group and it may manifest itself in suspicion of one group's activities by members of the other group, a desire to eliminate the presence of the group which is the target of suspicion, and fear of losing a national, ethnic, or racial identity.[5][6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xenophobia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/impact

See also

- Afrophobia, hostility towards Africa, Africans and people of African descent

- Anti-intellectualism

- Aporophobia, hostility towards poor people

- Authoritarian personality

- Black genocide conspiracy theory, the notion that African Americans have been subjected to genocide via birth control because of racism against African Americans

- Chauvinism

- Conformity

- Criticism of multiculturalism

- Cultural genocide

- Discrimination based on skin color

- Ethnic cleansing

- Ethnocentrism

- Eurabia, the belief that the culture of Europe is being Arabized and Islamized and the belief that Europe's previous alliances with the United States and Israel are being undermined

- European Commission against Racism and Intolerance

- Forced assimilation

- Genocide

- Great replacement, a variant of the white genocide conspiracy theory

- Hispanophobia, hostility towards Spaniards, hostility towards people of Spanish descent, dislike of Spanish culture, dislike of Spain and dislike of the Spanish language

- Index of racism-related articles

- Kalergi Plan conspiracy theory

- List of phobias

- Nationalism

- Nativism (politics)

- Negrophobia (also termed anti-Blackness) is characterized by fear of, hatred of or extreme aversion to Black people and Cape Coloureds or Coloureds, and Black & Colored culture

- Opposition to immigration

- Racism

- Stranger danger

- Supremacism

- Überfremdung, a German term for excessive immigration

- Xenocentrism

- Xenophilia

- Xenoracism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xenophobia

A preemptive arrest is one in which a person is arrested prior to committing a crime. Preemptive arrests are sometimes viewed with suspicion as being contrary to the principles of a democracy.[1]

This practice is distinct from an arrest on a charge of conspiracy to commit a crime, which for example in the United States federal system is itself a crime. A conspiracy charge in this system must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt, and requires that two or more parties have agreed to or planned to commit a crime and have taken concrete action to advance this plot.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Preemptive_arrest

An arrest without warrant or a warrantless arrest is an arrest of an individual without the use of an arrest warrant.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arrest_without_warrant

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:United_States_criminal_law

The power of arrest is a mandate given by a central authority that allows an individual to remove a criminal's (or suspected criminal's) liberty. The power of arrest can also be used to protect a person, or persons from harm or to protect damage to property.

However, in many countries, a person also has powers of arrest under citizen's arrest or any person arrest / breach of the peace arrest powers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_of_arrest

A citizen's arrest is an arrest made by a private citizen – that is, a person who is not acting as a sworn law-enforcement official.[1] In common law jurisdictions, the practice dates back to medieval England and the English common law, in which sheriffs encouraged ordinary citizens to help apprehend law breakers.[2]

Despite the practice's name, in most countries, the arresting person is usually designated as a person with arrest powers, who need not be a citizen of the country in which they are acting. For example, in the British jurisdiction of England and Wales, the power comes from section 24A(2) of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984,[3] called "any person arrest". This legislation states "any person" has these powers, and does not state that they need to be a British citizen.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Citizen%27s_arrest

Justification may refer to:

- Justification (epistemology), a property of beliefs that a person has good reasons for holding

- Justification (jurisprudence), defence in a prosecution for a criminal offenses

- Justification (theology), God's act of declaring or making a sinner righteous before God

- Justification (typesetting), a kind of typographic alignment

- Rationalization (making excuses), a phenomenon in psychology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Justification

A missing person is a person who has disappeared and whose status as alive or dead cannot be confirmed as their location and condition are unknown. A person may go missing through a voluntary disappearance, or else due to an accident, crime, death in a location where they cannot be found (such as at sea), or many other reasons. In most parts of the world, a missing person will usually be found quickly. While criminal abductions are some of the most widely reported missing person cases, these account for only 2–5% of missing children in Europe.[citation needed]

By contrast, some missing person cases remain unresolved for many years. Laws related to these cases are often complex since, in many jurisdictions, relatives and third parties may not deal with a person's assets until their death is considered proven by law and a formal death certificate issued. The situation, uncertainties, and lack of closure or a funeral resulting when a person goes missing may be extremely painful with long-lasting effects on family and friends.

A number of organizations seek to connect, share best practices, and disseminate information and images of missing children to improve the effectiveness of missing children investigations, including the International Commission on Missing Persons, the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children (ICMEC), as well as national organizations, including the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children in the US, Missing People in the UK, Child Focus in Belgium, and The Smile of the Child in Greece.

Reasons

People disappear for many reasons. Some individuals choose to disappear, for others disappearance is inadvertent (e.g. getting lost) or it is imposed on them (abduction/imprisonment). Reasons for disappearance may include:[1][2][3]

- To escape domestic abuse.

- Leaving home to live in an unknown place under a new identity.

- Becoming the victim of kidnapping.

- Child abduction by a non-custodial parent or other relative.

- Seizure by the federal authorities (Military, law enforcement, government) and imprisoned / detained indefinitely / tortured fatally / non fatally for an unknown period of time in an undisclosed guarded location without due process of law (see forced disappearance).

- Suicide in a remote location or under an assumed name (generally to spare their families the suicide at home or to allow their deaths to be eventually declared in absentia).

- Victim of murder (body disguised, destroyed, or hidden).

- Mental illness or other ailments such as Alzheimer's disease can cause people to forget where or who they are.

- Death by natural causes (disease) or accident far from home without identification.

- Becoming lost accidentally in remote areas, including when participating in outdoor recreation or labour (hiking, mountaineering, hunting, etc.)

- Disappearance to take advantage of better employment or living conditions elsewhere.

- Sold into slavery, serfdom, sexual servitude, or other unfree labor.

- To avoid discovery of a crime or apprehension by law-enforcement authorities, (See also failure to appear.) and punishment after committing a such crime (murder, theft, rape, terrorism, fraud, etc.).

- Joining a cult or other religious organization that requires no contact to the outside world.

- To avoid war or persecution during a genocide.

- As a consequence of war - e.g. missing in action, impressment, collateral damage

- To escape famine or natural disaster.

- Death by floods, flash floods, debris flows, hurricanes, tsunamis and tornadoes.

- Death in the water, with no body recovered.

- Aviation accident where no wreckage is found or ship wreck where no wreckage is found

- Desertion during war or absent without leave (AWOL).

- To avoid conscription.

- Hostage.

- To avoid paying someone or something.

Categories of missing children

- Runaways: Minors who run away from home, from the institution where they have been placed, or from the people responsible for their care.

- Thrownaways: Minors who are abandoned by their parents or guardians.

- Parental abduction: Minors who are abducted by their parents or guardians for unknown reasons.

- Non-parental abduction: Minors who are abducted by non-parental means. (e.g. random kidnapping on streets by random people.)

- Missing unaccompanied migrant minors: Disappearances of migrant children, nationals of a country in which there is no free movement of persons, under the age of 18 who have been separated from both parents and are not being cared for by an adult, who by law is responsible for doing so.

- Lost, injured or otherwise missing children: Disappearances for no apparent reason of minors who got lost (e.g., young children at the seaside in summer) or hurt themselves and cannot be found immediately (e.g. accidents during sport activities, at youth camps, etc.), as well as children whose reason for disappearing has not yet been determined or found.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Missing_person

Legal aspects

A common misconception is that a person must be absent for at least 24 hours before being legally classed as missing, but this is rarely the case. Law enforcement agencies often stress that the case should be reported as early as possible.[4][5] In fact it is extremely crucial to report a missing person as soon as possible. This is in order to take immediate action in the vital first 48 hours after a person is declared missing. In these 48 hours the police will be able to interview any eyewitness and get any suspect descriptions while it is still fresh in their minds.

In most common law jurisdictions a missing person can be declared dead in absentia (or "legally dead") after seven years. This time frame may be reduced in certain cases, such as deaths in major battles or mass disasters such as the September 11 attacks.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Missing_person

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/spain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/russia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/niggers

A presumption of death occurs when a person is thought to be dead by a group of people despite the absence of direct proof of the person's death, such as the finding of remains (e.g., a corpse or skeleton) attributable to that person. Such a presumption is typically made by an individual when a person has been missing for an extended period and in the absence of any evidence that person is still alive—or after a shorter period, but where the circumstances surrounding a person's disappearance overwhelmingly support the belief that the person is dead (e.g., an airplane crash).

A declaration that a person is dead resembles other forms of "preventive adjudication", such as the declaratory judgment.[1] Different jurisdictions have different legal standards for obtaining such a declaration and in some jurisdictions a presumption of death may arise after a person has been missing under certain circumstances and a certain amount of time.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presumption_of_death

False imprisonment or unlawful imprisonment occurs when a person intentionally restricts another person’s movement within any area without legal authority, justification, or the restrained person's permission.[1] Actual physical restraint is not necessary for false imprisonment to occur. A false imprisonment claim may be made based upon private acts, or upon wrongful governmental detention. For detention by the police, proof of false imprisonment provides a basis to obtain a writ of habeas corpus.[2]

Under common law, false imprisonment is both a crime and a tort.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_imprisonment

False arrest, Unlawful arrest or Wrongful arrest is a common law tort, where a plaintiff alleges they were held in custody without probable cause, or without an order issued by a court of competent jurisdiction. Although it is possible to sue law enforcement officials for false arrest, the usual defendants in such cases are private security firms.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_arrest

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Police_and_Criminal_Evidence_Act_1984

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Firefighter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cloak

Ticket quotas are commonly defined as any establishment of a predetermined or specified number of traffic citations an officer must issue in a specified time.[1] Some police departments may set "productivity goals" but deny specific quotas.[2] In many places, such as California, Texas, and Florida, traffic ticket quotas are specifically prohibited by law or illegal.[3][4][5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ticket_quota

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states,[1] but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal persons.[2][3] A treaty may also be known as an international agreement, protocol, covenant, convention, pact, or exchange of letters, among other terms. However, only documents that are legally binding on the parties are considered treaties under international law.[4] Treaties vary on the basis of obligations (the extent to which states are bound to the rules), precision (the extent to which the rules are unambiguous), and delegation (the extent to which third parties have authority to interpret, apply and make rules).[1][5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty

In telecommunications, asynchronous communication is transmission of data, generally without the use of an external clock signal, where data can be transmitted intermittently rather than in a steady stream.[1] Any timing required to recover data from the communication symbols is encoded within the symbols.

The most significant aspect of asynchronous communications is that data is not transmitted at regular intervals, thus making possible variable bit rate, and that the transmitter and receiver clock generators do not have to be exactly synchronized all the time. In asynchronous transmission, data is sent one byte at a time and each byte is preceded by start and stop bits.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asynchronous_communication

Cave rescue is a highly specialized field of wilderness rescue in which injured, trapped or lost cave explorers are medically treated and extracted from various cave environments.

Cave rescue borrows elements from firefighting, confined space rescue, rope rescue and mountaineering techniques but has also developed its own special techniques and skills for performing work in conditions that are almost always difficult and demanding. Since cave accidents, on an absolute scale, are a very limited form of incident, and cave rescue is a very specialized skill, normal emergency staff are rarely employed in the underground elements of the rescue. Instead, this is usually undertaken by other experienced cavers who undergo regular training through their organizations and are called up at need.

Cave rescues are slow, deliberate operations that require both a high level of organized teamwork and good communication. The extremes of the cave environment (air temperature, water, vertical depth) dictate every aspect of a cave rescue. Therefore, the rescuers must adapt skills and techniques that are as dynamic as the environment they must operate in.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cave_rescue

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_memory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Police_grade_mental_illness

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recall_(memory)

The encoding specificity principle is the general principle that matching the encoding contexts of information at recall assists in the retrieval of episodic memories. It provides a framework for understanding how the conditions present while encoding information relate to memory and recall of that information.[1]

It was introduced by Thomson and Tulving who suggested that contextual information is encoded with memories which affect the retrieval process. When a person uses information stored in their memory it is necessary that the information is accessible. The accessibility is governed by retrieval cues, these cues are dependent on the encoding pattern; the specific encoding pattern may vary from instance to instance, even if nominally the item is the same, as encoding depends on the context. This conclusion was drawn from a recognition-memory task.[2] A series of psychological experiments were undertaken in the 1970s which continued this work and further showed that context affects our ability to recall information.

The context may refer to the context in which the information was encoded, the physical location or surroundings, as well as the mental or physical state of the individual at the time of encoding. This principle plays a significant role in both the concept of context-dependent memory and the concept of state-dependent memory.

Examples of the use of the encoding specificity principle include; studying in the same room as an exam is taken and the recall of information when intoxicated being easier when intoxicated again.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encoding_specificity_principle

The outshining hypothesis

The outshining hypothesis is the phenomenon by which context effects are absent as a result of a different cue (item cue) suppressing the weaker cue at retrieval. This "outshining" can also occur for item cues by stronger context cues.[22] It is based on the idea that a heavenly body is more difficult to see when it is obscured by a full moon. Similarly, incidental encoding of environmental context-dependent cues can be completely "outshone" when there are better cues available. However, these incidentally encoded environmental cues can be used to prompt memory recall if stronger cues are not present at encoding. A cue may be considered "better" simply because it has been more deeply processed, repeated more often, or has fewer items associated with it.[21] As an example, a study by Steuck and Levy showed that environmental context-dependent memory has a decreased effect in word recall tests if the words are embedded into meaningful text.[21] This is because meaningful texts are stored better in memory and are more deeply processed.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Context-dependent_memory#The_outshining_hypothesis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memory

Unreported missing (also known as missing missing[1]) describes persons who cannot be found, yet have not been or cannot be reported as missing persons to law enforcement, specifically the National Crime Information Center database of missing persons in the United States. The term applies whether the missing person is a child or an adult.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unreported_missing

A do-not-resuscitate order (DNR), also known as Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR), Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR[3]), no code[4][5] or allow natural death, is a medical order, written or oral depending on country, indicating that a person should not receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if that person's heart stops beating.[5] Sometimes these decisions and the relevant documents also encompass decisions around other critical or life-prolonging medical interventions.[6] The legal status and processes surrounding DNR orders vary from country to country. Most commonly, the order is placed by a physician based on a combination of medical judgement and patient involvement.[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Do_not_resuscitate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Euthanasia

An advance healthcare directive, also known as living will, personal directive, advance directive, medical directive or advance decision, is a legal document in which a person specifies what actions should be taken for their health if they are no longer able to make decisions for themselves because of illness or incapacity. In the U.S. it has a legal status in itself, whereas in some countries it is legally persuasive without being a legal document.

A living will is one form of advance directive, leaving instructions for treatment. Another form is a specific type of power of attorney or health care proxy, in which the person authorizes someone (an agent) to make decisions on their behalf when they are incapacitated. People are often encouraged to complete both documents to provide comprehensive guidance regarding their care, although they may be combined into a single form. An example of combination documents includes the Five Wishes in the United States. The term living will is also the commonly recognised vernacular in many countries, especially the U.K.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advance_healthcare_directive

Override may refer to:

- Dr. Gregory Herd, a Marvel Comics character formerly named Override

- Manual override, a function where an automated system is placed under manual control

- Method overriding, a subclassing feature in Object Oriented programming languages.

- Price override, in retail

- Override, a character on the anime television series Transformers: Cybertron

- Override (film), a 1994 science fiction short film

- Override, a 2021 British science fiction thriller film

- OverRide (video game)

- Overrider, a Marvel Comics mutant

- Overriders, an insurance term

- Overriding (mathematics)

- Overriding aorta, a medical condition in which aorta emerge from abnormal position.

- Veto override, a procedure employed by legislatures

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Override

In contract law, a non-compete clause (often NCC), restrictive covenant, or covenant not to compete (CNC), is a clause under which one party (usually an employee) agrees not to enter into or start a similar profession or trade in competition against another party (usually the employer). Some courts refer to these as "restrictive covenants". As a contract provision, a CNC is bound by traditional contract requirements including the consideration doctrine.

The use of such clauses is premised on the possibility that upon their termination or resignation, an employee might begin working for a competitor or start a business, and gain competitive advantage by exploiting confidential information about their former employer's operations or trade secrets, or sensitive information such as customer/client lists, business practices, upcoming products, and marketing plans.

However, an over-broad CNC may prevent an employee from working elsewhere at all. English common law originally held any such constraint to be unenforceable under the public policy doctrine.[1] Contemporary case law permits exceptions, but generally will only enforce CNCs to the extent necessary to protect the employer. Most jurisdictions in which such contracts have been examined by the courts have deemed CNCs to be legally binding so long as the clause contains reasonable limitations as to the geographical area and time period in which an employee of a company may not compete.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-compete_clause

The non-cooperation movement of 1971 was a historical movement in then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) by the Awami League and the general public against the military government of Pakistan in March of that year. After the announcement of the suspension of the session of the National Assembly of Pakistan on March 1, the spontaneous movement of the people started, but officially on the call of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the non-cooperation movement started on March 2[1] and continued until March 25. The movement lasted for a total of 25 days.[2] The main objective of this movement was to ensure the autonomy of East Pakistan from the central government of Pakistan.[3][4] During this period, the control of the central government of West Pakistan over the civilian administration of East Pakistan was almost non-existent. At one stage of the movement, the whole of East Pakistan (except the cantonments) was practically under the command of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.[1][5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-cooperation_movement_(1971)

Introduction

A non-cooperative game is a form of game under the topic of game theory. Non-cooperative games are used in situations where there are competition between the players of the game. In this model, there are no external rules that enforces the cooperation of the players therefore it is typically used to model a competitive environment. This is stated in various accounts most prominent being John Nash's paper.[1]

That being said, there are many arguments to be made regarding this point as with decades of research, it is shown that non-cooperative game models can be used to show cooperation as well and vice versa for cooperative game model being used to show competition.

Some examples of this would be the usage of non-cooperative model in determining the stability and sustainability of cartels and coalitions.[2][3]

Non zero-sum games and zero-sum games are both types of non-cooperative games.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-cooperative_game_theory

Zero-sum game is a mathematical representation in game theory and economic theory of a situation that involves two sides, where the result is an advantage for one side and an equivalent loss for the other.[1] In other words, player one's gain is equivalent to player two's loss, with the result that the net improvement in benefit of the game is zero.[2]

If the total gains of the participants are added up, and the total losses are subtracted, they will sum to zero. Thus, cutting a cake, where taking a more significant piece reduces the amount of cake available for others as much as it increases the amount available for that taker, is a zero-sum game if all participants value each unit of cake equally. Other examples of zero-sum games in daily life include games like poker, chess, and bridge where one person gains and another person loses, which results in a zero-net benefit for every player.[3] In the markets and financial instruments, futures contracts and options are zero-sum games as well.[4]

In contrast, non-zero-sum describes a situation in which the interacting parties' aggregate gains and losses can be less than or more than zero. A zero-sum game is also called a strictly competitive game, while non-zero-sum games can be either competitive or non-competitive. Zero-sum games are most often solved with the minimax theorem which is closely related to linear programming duality,[5] or with Nash equilibrium. Prisoner's Dilemma is a classic non-zero-sum game.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zero-sum_game

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Non-cooperative_games

Detainer (from detain, Latin detinere); originally in British law, the act of keeping a person against his will, or the wrongful keeping of a person's goods, or other real or personal property. A writ of detainer was a form for the beginning of a personal action against a person already lodged within the walls of a prison; it was superseded by the Judgments Act 1838.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Detainer

Detention is the process whereby a state or private citizen lawfully holds a person by removing their freedom or liberty at that time. This can be due to (pending) criminal charges preferred against the individual pursuant to a prosecution or to protect a person or property. Being detained does not always result in being taken to a particular area (generally called a detention centre), either for interrogation or as punishment for a crime (see prison). An individual may be detained due a psychiatric disorder, potentially to treat this disorder involuntarily.[2] They may also be detained for to prevent the spread of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Detention_(imprisonment)

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges[1] or intent to file charges.[2] The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects".[3] Thus, while it can simply mean imprisonment, it tends to refer to preventive confinement rather than confinement after having been convicted of some crime. Use of these terms is subject to debate and political sensitivities.[4] The word internment is also occasionally used to describe a neutral country's practice of detaining belligerent armed forces and equipment on its territory during times of war, under the Hague Convention of 1907.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internment

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (German: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (Todeslager), or killing centers (Tötungszentren), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million people – mostly Jews – in the Holocaust.[1][2][3] The victims of death camps were primarily murdered by gassing, either in permanent installations constructed for this specific purpose, or by means of gas vans.[4] The six extermination camps were Chełmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Extermination through labour was also used at the Auschwitz and Majdanek death camps.[5][6][4] Millions were also murdered in concentration camps, in the Aktion T4 or murdered directly on side.[7]

The idea of mass extermination with the use of stationary facilities, to which the victims were taken by train, was the result of earlier Nazi experimentation with chemically manufactured poison gas during the secretive Aktion T4 euthanasia programme against hospital patients with mental and physical disabilities.[8] The technology was adapted, expanded, and applied in wartime to unsuspecting victims of many ethnic and national groups; the Jews were the primary target, accounting for over 90 percent of extermination camp victims.[9] The genocide of the Jews of Europe was Nazi Germany's "Final Solution to the Jewish question".[10][4][11]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extermination_camp

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.[1]

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre is an ancient tradition. Starting in the 19th century, cremation was introduced or reintroduced into other parts of the world. In modern times, cremation is commonly carried out with a closed furnace (cremator), at a crematorium.

Cremation leaves behind an average of 2.4 kg (5.3 lbs) of remains known as "ashes" or "cremains". This is not all ash but includes unburnt fragments of bone mineral, which are commonly ground into powder. They do not constitute a health risk and may be buried, interred in a memorial site, retained by relatives or scattered in various ways.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cremation

History

Ancient

Cremation dates from at least 17,000 years ago[2][3] in the archaeological record, with the Mungo Lady, the remains of a partly cremated body found at Lake Mungo, Australia.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cremation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Death_customs

Category:Fire

- For specific fires that have occurred, see Category:Fires.

Subcategories

This category has the following 17 subcategories, out of 17 total.

- Fires (10 C, 1 P)

*

- Types of fire (28 P)

A

- Arson (10 C, 5 P)

C

- Fire in culture (8 C, 14 P)

D

- Deaths from fire (6 C, 157 P)

F

- Furnaces (4 C, 9 P)

I

- Incineration (2 C, 18 P)

L

- Firelighting (7 C, 16 P)

P

- Fire protection (5 C, 69 P)

S

- Smoke (6 C, 37 P)

Pages in category "Fire"

The following 71 pages are in this category, out of 71 total. This list may not reflect recent changes.

B

E

F

H

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Fire

In computer science, brute-force search or exhaustive search, also known as generate and test, is a very general problem-solving technique and algorithmic paradigm that consists of systematically enumerating all possible candidates for the solution and checking whether each candidate satisfies the problem's statement.

A brute-force algorithm that finds the divisors of a natural number n would enumerate all integers from 1 to n, and check whether each of them divides n without remainder. A brute-force approach for the eight queens puzzle would examine all possible arrangements of 8 pieces on the 64-square chessboard and for each arrangement, check whether each (queen) piece can attack any other.[1]

While a brute-force search is simple to implement and will always find a solution if it exists, implementation costs are proportional to the number of candidate solutions – which in many practical problems tends to grow very quickly as the size of the problem increases (§Combinatorial explosion).[2] Therefore, brute-force search is typically used when the problem size is limited, or when there are problem-specific heuristics that can be used to reduce the set of candidate solutions to a manageable size. The method is also used when the simplicity of implementation is more important than speed.

This is the case, for example, in critical applications where any errors in the algorithm would have very serious consequences or when using a computer to prove a mathematical theorem. Brute-force search is also useful as a baseline method when benchmarking other algorithms or metaheuristics. Indeed, brute-force search can be viewed as the simplest metaheuristic. Brute force search should not be confused with backtracking, where large sets of solutions can be discarded without being explicitly enumerated (as in the textbook computer solution to the eight queens problem above). The brute-force method for finding an item in a table – namely, check all entries of the latter, sequentially – is called linear search.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brute-force_search

An uninterruptible power supply or uninterruptible power source (UPS) is an electrical apparatus that provides emergency power to a load when the input power source or mains power fails. A UPS differs from an auxiliary or emergency power system or standby generator in that it will provide near-instantaneous protection from input power interruptions, by supplying energy stored in batteries, supercapacitors, or flywheels. The on-battery run-time of most uninterruptible power sources is relatively short (only a few minutes) but sufficient to start a standby power source or properly shut down the protected equipment. It is a type of continual power system.

A UPS is typically used to protect hardware such as computers, data centers, telecommunication equipment or other electrical equipment where an unexpected power disruption could cause injuries, fatalities, serious business disruption or data loss. UPS units range in size from ones designed to protect a single computer without a video monitor (around 200 volt-ampere rating) to large units powering entire data centers or buildings. The world's largest UPS, the 46-megawatt Battery Energy Storage System (BESS), in Fairbanks, Alaska, powers the entire city and nearby rural communities during outages.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uninterruptible_power_supply

In linguistic morphology, an uninflected word is a word that has no morphological markers (inflection) such as affixes, ablaut, consonant gradation, etc., indicating declension or conjugation. If a word has an uninflected form, this is usually the form used as the lemma for the word.[1]

In English and many other languages, uninflected words include prepositions, interjections, and conjunctions, often called invariable words. These cannot be inflected under any circumstances (unless they are used as different parts of speech, as in "ifs and buts").

Only words that cannot be inflected at all are called "invariable". In the strict sense of the term "uninflected", only invariable words are uninflected, but in broader linguistic usage, these terms are extended to be inflectable words that appear in their basic form. For example, English nouns are said to be uninflected in the singular, while they show inflection in the plural (represented by the affix -s/-es). The term "uninflected" can also refer to uninflectability with respect to one or more, but not all, morphological features; for example, one can say that Japanese verbs are uninflected for person and number, but they do inflect for tense, politeness, and several moods and aspects.

In the strict sense, among English nouns only mass nouns (such as sand, information, or equipment) are truly uninflected, since they have only one form that does not change; count nouns are always inflected for number, even if the singular inflection is shown by an "invisible" affix (the null morpheme). In the same way, English verbs are inflected for person and tense even if the morphology showing those categories is realized as null morphemes. In contrast, other analytic languages like Mandarin Chinese have true uninflected nouns and verbs, where the notions of number and tense are completely absent.

In many inflected languages, such as Greek and Russian, some nouns and adjectives of foreign origin are left uninflected in contexts where native words would be inflected; for instance, the name Abraam in Greek (from Hebrew), the Modern Greek word μπλε ble (from French bleu), the Italian word computer, and the Russian words кенгуру, kenguru (kangaroo) and пальто, pal'to (coat, from French paletot).

In German, all modal particles are uninflected.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uninflected_word

In morphology, a null morpheme or zero morpheme is a morpheme that has no phonetic form.[1] In simpler terms, a null morpheme is an "invisible" affix. It is a concept useful for analysis, by contrasting null morphemes with alternatives that do have some phonetic realization.[2] The null morpheme is represented as either the figure zero (0) or the empty set symbol ∅.

In most languages, it is the affixes that are realized as null morphemes, indicating that the derived form does not differ from the stem. For example, plural form sheep can be analyzed as combination of sheep with added null affix for the plural. The process of adding a null affix is called null affixation, null derivation or zero derivation. The concept was first used by the 4th century BCE Sanskrit grammarian from ancient India, Pāṇini, in his Sanskrit grammar.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Null_morpheme

A prior probability distribution of an uncertain quantity, often simply called the prior, is its assumed probability distribution before some evidence is taken into account. For example, the prior could be the probability distribution representing the relative proportions of voters who will vote for a particular politician in a future election. The unknown quantity may be a parameter of the model or a latent variable rather than an observable variable.

In Bayesian statistics, Bayes' rule prescribes how to update the prior with new information to obtain the posterior probability distribution, which is the conditional distribution of the uncertain quantity given new data. Historically, the choice of priors was often constrained to a conjugate family of a given likelihood function, for that it would result in a tractable posterior of the same family. The widespread availability of Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, however, has made this less of a concern.

There are many ways to construct a prior distribution.[1] In some cases, a prior may be determined from past information, such as previous experiments. A prior can also be elicited from the purely subjective assessment of an experienced expert.[2][3] When no information is available, an uninformative prior may be adopted as justified by the principle of indifference.[4][5] In modern applications, priors are also often chosen for their mechanical properties, such as regularization and feature selection.[6][7]

The prior distributions of model parameters will often depend on parameters of their own. Uncertainty about these hyperparameters can, in turn, be expressed as hyperprior probability distributions. For example, if one uses a beta distribution to model the distribution of the parameter p of a Bernoulli distribution, then:

- p is a parameter of the underlying system (Bernoulli distribution), and

- α and β are parameters of the prior distribution (beta distribution); hence hyperparameters.

In principle, priors can be decomposed into many conditional levels of distributions, so-called hierarchical priors.[8]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prior_probability

A Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) is a unique sequence of characters that identifies a logical or physical resource used by web technologies. URIs may be used to identify anything, including real-world objects, such as people and places, concepts, or information resources such as web pages and books. Some URIs provide a means of locating and retrieving information resources on a network (either on the Internet or on another private network, such as a computer filesystem or an Intranet); these are Uniform Resource Locators (URLs). A URL provides the location of the resource. A URI identifies the resource by name at the specified location or URL. Other URIs provide only a unique name, without a means of locating or retrieving the resource or information about it, these are Uniform Resource Names (URNs). The web technologies that use URIs are not limited to web browsers. URIs are used to identify anything described using the Resource Description Framework (RDF), for example, concepts that are part of an ontology defined using the Web Ontology Language (OWL), and people who are described using the Friend of a Friend vocabulary would each have an individual URI.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uniform_Resource_Identifier

This article lists forms of government and political systems, according to a series of different ways of categorizing them. The systems listed are not mutually exclusive, and often have overlapping definitions.[1]

According to Yale professor Juan José Linz there are three main types of political systems today: democracies, totalitarian regimes and, sitting between these two, authoritarian regimes with hybrid regimes.[2][3] Another modern classification system includes monarchies as a standalone entity or as a hybrid system of the main three.[4] Scholars generally refer to a dictatorship as either a form of authoritarianism or totalitarianism.[5][2][6]

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato discusses in the Republic five types of regimes: aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny. [7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_forms_of_government

State space search is a process used in the field of computer science, including artificial intelligence (AI), in which successive configurations or states of an instance are considered, with the intention of finding a goal state with the desired property.

Problems are often modelled as a state space, a set of states that a problem can be in. The set of states forms a graph where two states are connected if there is an operation that can be performed to transform the first state into the second.

State space search often differs from traditional computer science search methods because the state space is implicit: the typical state space graph is much too large to generate and store in memory. Instead, nodes are generated as they are explored, and typically discarded thereafter. A solution to a combinatorial search instance may consist of the goal state itself, or of a path from some initial state to the goal state.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_space_search

Bidirectional search is a graph search algorithm that finds a shortest path from an initial vertex to a goal vertex in a directed graph. It runs two simultaneous searches: one forward from the initial state, and one backward from the goal, stopping when the two meet. The reason for this approach is that in many cases it is faster: for instance, in a simplified model of search problem complexity in which both searches expand a tree with branching factor b, and the distance from start to goal is d, each of the two searches has complexity O(bd/2) (in Big O notation), and the sum of these two search times is much less than the O(bd) complexity that would result from a single search from the beginning to the goal.

Andrew Goldberg and others explained the correct termination conditions for the bidirectional version of Dijkstra’s Algorithm.[1]

As in A* search, bi-directional search can be guided by a heuristic estimate of the remaining distance to the goal (in the forward tree) or from the start (in the backward tree).

Ira Pohl (1971) was the first one to design and implement a bi-directional heuristic search algorithm. Search trees emanating from the start and goal nodes failed to meet in the middle of the solution space. The BHFFA algorithm fixed this defect Champeaux (1977).

A solution found by the uni-directional A* algorithm using an admissible heuristic has a shortest path length; the same property holds for the BHFFA2 bidirectional heuristic version described in de Champeaux (1983). BHFFA2 has, among others, more careful termination conditions than BHFFA.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bidirectional_search

Incremental heuristic search algorithms combine both incremental and heuristic search to speed up searches of sequences of similar search problems, which is important in domains that are only incompletely known or change dynamically.[1] Incremental search has been studied at least since the late 1960s. Incremental search algorithms reuse information from previous searches to speed up the current search and solve search problems potentially much faster than solving them repeatedly from scratch.[2] Similarly, heuristic search has also been studied at least since the late 1960s.

Heuristic search algorithms, often based on A*, use heuristic knowledge in the form of approximations of the goal distances to focus the search and solve search problems potentially much faster than uninformed search algorithms.[3] The resulting search problems, sometimes called dynamic path planning problems, are graph search problems where paths have to be found repeatedly because the topology of the graph, its edge costs, the start vertex or the goal vertices change over time.[4]

So far, three main classes of incremental heuristic search algorithms have been developed:

- The first class restarts A* at the point where its current search deviates from the previous one (example: Fringe Saving A*[5]).

- The second class updates the h-values (heuristic, i.e. approximate distance to goal) from the previous search during the current search to make them more informed (example: Generalized Adaptive A*[6]).

- The third class updates the g-values (distance from start) from the previous search during the current search to correct them when necessary, which can be interpreted as transforming the A* search tree from the previous search into the A* search tree for the current search (examples: Lifelong Planning A*,[7] D*,[8] D* Lite[9]).

All three classes of incremental heuristic search algorithms are different from other replanning algorithms, such as planning by analogy, in that their plan quality does not deteriorate with the number of replanning episodes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incremental_heuristic_search

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the United States federal government, tasked with gathering, processing, and analyzing national security information from around the world.

The National Resources Division is the domestic wing of the CIA. Although the CIA is focused on gathering intelligence from foreign nations, it has performed operations within the United States to achieve its goals. Some of these operations only became known to the public years after they had been conducted, and were met with significant criticism from the population as a whole, with allegations that these operations may violate the Constitution.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CIA_activities_in_the_United_States

Theoretic suitability for search

Different scholars provided the theoretic support to argue the suitability of folksonomies as a navigational aid. There are four main perspectives:

- Network theoretic perspective has two aspects: the general navigability of a folksonomy as a graph, or the ability of tag hierarchies to guide navigation in such a graph

- Information theoretic perspective suggest to see social tagging as the collective effort of creating a mental map that summarize an information space

- Information foraging perspective to describe the human information seeking in a digital environment

- Tagging vs. library approach. They[who?] proposed a definition of a controlled vocabulary and compared unrestricted free-form vocabularies emerged in social tagging systems to controlled vocabularies

Pragmatic folksonomy evaluation

The evaluation method introduced in this section is based on the paper by Helic et al.[30] The author proposed in the paper the general idea that people can leverage on the output produced by folksonomy algorithms (hierarchical structures) as input (background knowledge) for decentralized search for the following reasons:

- The performance of decentralized search highly depends on the quality of the hierarchical clustering results that developed to facilitated navigation.

- The performance of the decentralized search algorithm depends on the suitability of folksonomies.

- The authors proposed the simulation method on decentralized search can be leveraged to evaluate the suitability of folksonomies.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_navigation#Theoretic_suitability_for_search

The FBI Laboratory (also called the Laboratory Division)[2] is a division within the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation that provides forensic analysis support services to the FBI, as well as to state and local law enforcement agencies free of charge. The lab is located at Marine Corps Base Quantico in Quantico, Virginia. Opened November 24, 1932,[3] the lab was first known as the Technical Laboratory. It became a separate division when the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) was renamed as the FBI.

The Lab staffs approximately 500 scientific experts and special agents. The lab generally enjoys the reputation as the premier crime lab in the United States. However, during the 1990s, its reputation and integrity came under withering criticism, primarily due to the revelations of Special Agent Dr. Frederic Whitehurst, the most prominent whistleblower in the history of the Bureau. Whitehurst was a harsh critic of conduct at the Lab. He believed that a lack of funding had affected operations and that Lab technicians had a pro-prosecution bias. He suggested they were FBI agents first and forensic scientists second, due to the institutional culture of the Bureau, which resulted in the tainting of evidence.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FBI_Laboratory

Herd behavior is the behavior of individuals in a group acting collectively without centralized direction. Herd behavior occurs in animals in herds, packs, bird flocks, fish schools and so on, as well as in humans. Voting, demonstrations, riots, general strikes,[1] sporting events, religious gatherings, everyday decision-making, judgement and opinion-forming, are all forms of human-based herd behavior.

Raafat, Chater and Frith proposed an integrated approach to herding, describing two key issues, the mechanisms of transmission of thoughts or behavior between individuals and the patterns of connections between them.[2] They suggested that bringing together diverse theoretical approaches of herding behavior illuminates the applicability of the concept to many domains, ranging from cognitive neuroscience to economics.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herd_behavior