https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Measurement

In master locksmithing, key relevance is the measurable difference between an original key and a copy made of that key, either from a wax impression or directly from the original, and how similar the two keys are in size and shape.[1] It can also refer to the measurable difference between a key and the size required to fit and operate the keyway of its paired lock.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Key_relevance

Level of measurement or scale of measure is a classification that describes the nature of information within the values assigned to variables.[1] Psychologist Stanley Smith Stevens developed the best-known classification with four levels, or scales, of measurement: nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio.[1][2] This framework of distinguishing levels of measurement originated in psychology and has since had a complex history, being adopted and extended in some disciplines and by some scholars, and criticized or rejected by others.[3] Other classifications include those by Mosteller and Tukey,[4] and by Chrisman.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Level_of_measurement

The limit of detection (LOD or LoD) is the lowest signal, or the lowest corresponding quantity to be determined (or extracted) from the signal, that can be observed with a sufficient degree of confidence or statistical significance. However, the exact threshold (level of decision) used to decide when a signal significantly emerges above the continuously fluctuating background noise remains arbitrary and is a matter of policy and often of debate among scientists, statisticians and regulators depending on the stakes in different fields.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Detection_limit

In the branch of experimental psychology focused on sense, sensation, and perception, which is called psychophysics, a just-noticeable difference or JND is the amount something must be changed in order for a difference to be noticeable, detectable at least half the time.[1] This limen is also known as the difference limen, difference threshold, or least perceptible difference.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Just-noticeable_difference

An environmental error is an error in calculations that are being a part of observations due to environment. Any experiment performing anywhere in the universe has its surroundings, from which we cannot eliminate our system. The study of environmental effects has primary advantage of being able us to justify the fact that environment has impact on experiments and feasible environment will not only rectify our result but also amplify it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmental_error

In behavioral psychology (or applied behavior analysis), stimulus control is a phenomenon in operant conditioning (also called contingency management) that occurs when an organism behaves in one way in the presence of a given stimulus and another way in its absence. A stimulus that modifies behavior in this manner is either a discriminative stimulus (Sd) or stimulus delta (S-delta). Stimulus-based control of behavior occurs when the presence or absence of an Sd or S-delta controls the performance of a particular behavior. For example, the presence of a stop sign (S-delta) at a traffic intersection alerts the driver to stop driving and increases the probability that "braking" behavior will occur. Such behavior is said to be emitted because it does not force the behavior to occur since stimulus control is a direct result of historical reinforcement contingencies, as opposed to reflexive behavior that is said to be elicited through respondent conditioning.

Some theorists believe that all behavior is under some form of stimulus control.[1] For example, in the analysis of B. F. Skinner,[2] verbal behavior is a complicated assortment of behaviors with a variety of controlling stimuli.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stimulus_control

Extinction is a behavioral phenomenon observed in both operantly conditioned and classically conditioned behavior, which manifests itself by fading of non-reinforced conditioned response over time. When operant behavior that has been previously reinforced no longer produces reinforcing consequences the behavior gradually stops occurring.[1] In classical conditioning, when a conditioned stimulus is presented alone, so that it no longer predicts the coming of the unconditioned stimulus, conditioned responding gradually stops. For example, after Pavlov's dog was conditioned to salivate at the sound of a metronome, it eventually stopped salivating to the metronome after the metronome had been sounded repeatedly but no food came. Many anxiety disorders such as post traumatic stress disorder are believed to reflect, at least in part, a failure to extinguish conditioned fear.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extinction_(psychology)

Discrimination is the act of making distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong that are disadvantageous.[1] People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender identity, sex, age, religion, disability, or sexual orientation, as well as other categories.[2] Discrimination especially occurs when individuals or groups are unfairly treated in a way which is worse than other people are treated, on the basis of their actual or perceived membership in certain groups or social categories.[2][3] It involves restricting members of one group from opportunities or privileges that are available to members of another group.[4]

Discriminatory traditions, policies, ideas, practices and laws exist in many countries and institutions in all parts of the world, including territories where discrimination is generally looked down upon. In some places, attempts such as quotas have been used to benefit those who are believed to be current or past victims of discrimination. These attempts have often been met with controversy, and have sometimes been called reverse discrimination.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discrimination

In digital audio using pulse-code modulation (PCM), bit depth is the number of bits of information in each sample, and it directly corresponds to the resolution of each sample. Examples of bit depth include Compact Disc Digital Audio, which uses 16 bits per sample, and DVD-Audio and Blu-ray Disc which can support up to 24 bits per sample.

In basic implementations, variations in bit depth primarily affect the noise level from quantization error—thus the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and dynamic range. However, techniques such as dithering, noise shaping, and oversampling can mitigate these effects without changing the bit depth. Bit depth also affects bit rate and file size.

Bit depth is only meaningful in reference to a PCM digital signal. Non-PCM formats, such as lossy compression formats, do not have associated bit depths.[a]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Audio_bit_depth

Image resolution is the detail an image holds. The term applies to digital images, film images, and other types of images. "Higher resolution" means more image detail.

Image resolution can be measured in various ways. Resolution quantifies how close lines can be to each other and still be visibly resolved. Resolution units can be tied to physical sizes (e.g. lines per mm, lines per inch), to the overall size of a picture (lines per picture height, also known simply as lines, TV lines, or TVL), or to angular subtense. Instead of single lines, line pairs are often used, composed of a dark line and an adjacent light line; for example, a resolution of 10 lines per millimeter means 5 dark lines alternating with 5 light lines, or 5 line pairs per millimeter (5 LP/mm). Photographic lens and are most often quoted in line pairs per millimeter.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image_resolution

Gestalt psychology, gestaltism, or configurationism is a school of psychology that emerged in the early twentieth century in Austria and Germany as a theory of perception that was a rejection of basic principles of Wilhelm Wundt's and Edward Titchener's elementalist and structuralist psychology.[1][2][3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gestalt_psychology

In psychology and cognitive science, a schema (plural schemata or schemas) describes a pattern of thought or behavior that organizes categories of information and the relationships among them.[1][2] It can also be described as a mental structure of preconceived ideas, a framework representing some aspect of the world, or a system of organizing and perceiving new information,[3] such as a mental schema or conceptual model. Schemata influence attention and the absorption of new knowledge: people are more likely to notice things that fit into their schema, while re-interpreting contradictions to the schema as exceptions or distorting them to fit. Schemata have a tendency to remain unchanged, even in the face of contradictory information.[4] Schemata can help in understanding the world and the rapidly changing environment.[5] People can organize new perceptions into schemata quickly as most situations do not require complex thought when using schema, since automatic thought is all that is required.[5]

People use schemata to organize current knowledge and provide a framework for future understanding. Examples of schemata include mental models, social schemas, stereotypes, social roles, scripts, worldviews, heuristics, and archetypes. In Piaget's theory of development, children construct a series of schemata, based on the interactions they experience, to help them understand the world.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schema_(psychology)

The earliest recorded systems of weights and measures originate in the 3rd or 4th millennium BC. Even the very earliest civilizations needed measurement for purposes of agriculture, construction and trade. Early standard units might only have applied to a single community or small region, with every area developing its own standards for lengths, areas, volumes and masses. Often such systems were closely tied to one field of use, so that volume measures used, for example, for dry grains were unrelated to those for liquids, with neither bearing any particular relationship to units of length used for measuring cloth or land. With development of manufacturing technologies, and the growing importance of trade between communities and ultimately across the Earth, standardized weights and measures became critical. Starting in the 18th century, modernized, simplified and uniform systems of weights and measures were developed, with the fundamental units defined by ever more precise methods in the science of metrology. The discovery and application of electricity was one factor motivating the development of standardized internationally applicable units.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_measurement

The history of science and technology (HST) is a field of history that examines the understanding of the natural world (science) and the ability to manipulate it (technology) at different points in time. This academic discipline also studies the cultural, economic, and political impacts of and contexts for scientific practices.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_science_and_technology

Instrumentation is a collective term for measuring instruments that are used for indicating, measuring and recording physical quantities. The term has its origins in the art and science of scientific instrument-making.

Instrumentation can refer to devices as simple as direct-reading thermometers, or as complex as multi-sensor components of industrial control systems. Today, instruments can be found in laboratories, refineries, factories and vehicles, as well as in everyday household use (e.g., smoke detectors and thermostats)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instrumentation

ISO 10012:2003, Measurement management systems - Requirements for measurement processes and measuring equipment is the ISO standard that specifies generic requirements and provides guidance for the management of measurement processes and metrological confirmation of measuring equipment used to support and demonstrate compliance with metrological requirements. It specifies quality management requirements of a measurement management system that can be used by an organization performing measurements as part of the overall management system, and to ensure metrological requirements are met.

ISO 10012:2003 is not intended to be used as a requisite for demonstrating conformance with ISO 9001, ISO 14001 or any other standard. Interested parties can agree to use ISO 10012:2003 as an input for satisfying measurement management system requirements in certification activities.

Other standards and guides exist for particular elements affecting measurement results, e.g. details of measurement methods, competence of personnel, and interlaboratory comparisons.

ISO 10012:2003 is not intended as a substitute for, or as an addition to, the requirements of ISO/IEC 17025.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISO_10012

A primary instrument is a scientific instrument, which by its physical characteristics is accurate and is not calibrated against anything else. A primary instrument must be able to be exactly duplicated anywhere, anytime with identical results.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primary_instrument

An order of magnitude is an approximation of the logarithm of a value relative to some contextually understood reference value, usually 10, interpreted as the base of the logarithm and the representative of values of magnitude one. Logarithmic distributions are common in nature and considering the order of magnitude of values sampled from such a distribution can be more intuitive. When the reference value is 10, the order of magnitude can be understood as the number of digits in the base-10 representation of the value. Similarly, if the reference value is one of some powers of 2, since computers store data in a binary format, the magnitude can be understood in terms of the amount of computer memory needed to store that value.

Differences in order of magnitude can be measured on a base-10 logarithmic scale in “decades” (i.e., factors of ten).[1] Examples of numbers of different magnitudes can be found at Orders of magnitude (numbers).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_magnitude

In statistics, latent variables (from Latin: present participle of lateo, “lie hidden”) are variables that can only be inferred indirectly through a mathematical model from other observable variables that can be directly observed or measured.[1] Such latent variable models are used in many disciplines, including political science, demography, engineering, medicine, ecology, physics, machine learning/artificial intelligence, bioinformatics, chemometrics, natural language processing, management and the social sciences.

Latent variables may correspond to aspects of physical reality. These could in principle be measured, but may not be for practical reasons. In this situation, the term hidden variables is commonly used (reflecting the fact that the variables are meaningful, but not observable). Other latent variables correspond to abstract concepts, like categories, behavioral or mental states, or data structures. The terms hypothetical variables or hypothetical constructs may be used in these situations.

The use of latent variables can serve to reduce the dimensionality of data. Many observable variables can be aggregated in a model to represent an underlying concept, making it easier to understand the data. In this sense, they serve a function similar to that of scientific theories. At the same time, latent variables link observable "sub-symbolic" data in the real world to symbolic data in the modeled world.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latent_and_observable_variables

Hidden variables may refer to:

- Confounding, in statistics, an extraneous variable in a statistical model that correlates (directly or inversely) with both the dependent variable and the independent variable

- Hidden transformation, in computer science, a way to transform a generic constraint satisfaction problem into a binary one by introducing new hidden variables

- Hidden-variable theories,

in physics, the proposition that statistical models of physical systems

(such as Quantum mechanics) are inherently incomplete, and that the

apparent randomness of a system depends not on collapsing wave

functions, but rather due to unseen or unmeasurable (and thus "hidden")

variables

- Local hidden-variable theory, in quantum mechanics, a hidden-variable theory in which distant events are assumed to have no instantaneous (or at least faster-than-light) effect on local events

- Latent variables, in statistics, variables that are inferred from other observed variables

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hidden_variable

NCSL International (NCSLI) (from the founding name "National Conference of Standards Laboratories") is a global, non-profit organization whose membership is open to any organization with an interest in metrology (the science of measurement) and its application in research, development, education, and commerce.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NCSL_International

Measurement is a peer-reviewed scientific journal covering all aspects of metrology. It was established in 1983 and is published 18 times per year. It is published by Elsevier on behalf of the International Measurement Confederation and the editor-in-chief is Paolo Carbone (University of Perugia). According to the Journal Citation Reports, the journal has a 2021 impact factor of 5.131.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Measurement_(journal)

An unusual unit of measurement is a unit of measurement that does not form part of a coherent system of measurement, especially because its exact quantity may not be well known or because it may be an inconvenient multiple or fraction of a base unit.

Many of the unusual units of measurements listed here are colloquial measurements, units devised to compare a measurement to common and familiar objects.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_unusual_units_of_measurement

In the science of measurement, the least count of a measuring instrument is the smallest value in the measured quantity that can be resolved on the instrument's scale.[1] The least count is related to the precision of an instrument; an instrument that can measure smaller changes in a value relative to another instrument, has a smaller "least count" value and so is more precise. Any measurement made by the instrument can be considered repeatable to no less than the resolution of the least count. The least count of an instrument is inversely proportional to the precision of the instrument.

For example, a sundial may only have scale marks representing the hours of daylight; it would have a least count of one hour. A stopwatch used to time a race might resolve down to a hundredth of a second, its least count. The stopwatch is more precise at measuring time intervals than the sundial because it has more "counts" (scale intervals) in each hour of elapsed time. Least count of an instrument is one of the very important tools in order to get accurate readings of instruments like vernier caliper and screw gauge used in various experiments.

Least count uncertainty is one of the sources of experimental error in measurements. Least count of a vernier caliper is 0.1 mm and least count of a micrometer is 0.01 mm.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Least_count

In metrology (the science of measurement), a standard (or etalon) is an object, system, or experiment that bears a defined relationship to a unit of measurement of a physical quantity.[1] Standards are the fundamental reference for a system of weights and measures, against which all other measuring devices are compared. Historical standards for length, volume, and mass were defined by many different authorities, which resulted in confusion and inaccuracy of measurements. Modern measurements are defined in relationship to internationally standardized reference objects, which are used under carefully controlled laboratory conditions to define the units of length, mass, electrical potential, and other physical quantities.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_(metrology)

Timeline of temperature and pressure measurement technology. A history of temperature measurement and pressure measurement technology.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_temperature_and_pressure_measurement_technology

Virtual instrumentation is the use of customizable software and modular measurement hardware to create user-defined measurement systems, called virtual instruments.

Traditional hardware instrumentation systems are made up of fixed hardware components, such as digital multimeters and oscilloscopes that are completely specific to their stimulus, analysis, or measurement function. Because of their hard-coded function, these systems are more limited in their versatility than virtual instrumentation systems. The primary difference between hardware instrumentation and virtual instrumentation is that software is used to replace a large amount of hardware. The software enables complex and expensive hardware to be replaced by already purchased computer hardware; e. g. analog-to-digital converter can act as a hardware complement of a virtual oscilloscope, a potentiostat enables frequency response acquisition and analysis in electrochemical impedance spectroscopy with virtual instrumentation.

The concept of a synthetic instrument is a subset of the virtual instrument concept. A synthetic instrument is a kind of virtual instrument that is purely software defined. A synthetic instrument performs a specific synthesis, analysis, or measurement function on completely generic, measurement agnostic hardware. Virtual instruments can still have measurement specific hardware, and tend to emphasize modular hardware approaches that facilitate this specificity. Hardware supporting synthetic instruments is by definition not specific to the measurement, nor is it necessarily (or usually) modular.

Leveraging commercially available technologies, such as the PC and the analog-to-digital converter, virtual instrumentation has grown significantly since its inception in the late 1970s. Additionally, software packages like National Instruments' LabVIEW and other graphical programming languages helped grow adoption by making it easier for non-programmers to develop systems.

The newly updated technology called "HARD VIRTUAL INSTRUMENTATION" is developed by some companies. It is said that with this technology the execution of the software is done by the hardware itself which can help in fast real time processing.

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_instrumentation

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2019) |

A unit of measurement is a definite magnitude of a quantity, defined and adopted by convention or by law, that is used as a standard for measurement of the same kind of quantity.[1] Any other quantity of that kind can be expressed as a multiple of the unit of measurement.[2]

For example, a length is a physical quantity. The metre (symbol m) is a unit of length that represents a definite predetermined length. For instance, when referencing "10 metres" (or 10 m), what is actually meant is 10 times the definite predetermined length called "metre".

The definition, agreement, and practical use of units of measurement have played a crucial role in human endeavour from early ages up to the present. A multitude of systems of units used to be very common. Now there is a global standard, the International System of Units (SI), the modern form of the metric system.

In trade, weights and measures is often a subject of governmental regulation, to ensure fairness and transparency. The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) is tasked with ensuring worldwide uniformity of measurements and their traceability to the International System of Units (SI).

Metrology is the science of developing nationally and internationally accepted units of measurement.

In physics and metrology, units are standards for measurement of physical quantities that need clear definitions to be useful. Reproducibility of experimental results is central to the scientific method. A standard system of units facilitates this. Scientific systems of units are a refinement of the concept of weights and measures historically developed for commercial purposes.[3]

Science, medicine, and engineering often use larger and smaller units of measurement than those used in everyday life. The judicious selection of the units of measurement can aid researchers in problem solving (see, for example, dimensional analysis).

In the social sciences, there are no standard units of measurement and the theory and practice of measurement is studied in psychometrics and the theory of conjoint measurement.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unit_of_measurement

Metric fixation refers to a tendency for decision-makers to place excessively large emphases on selected metrics.

In management (and many other social science fields), decision makers typically use metrics to measure how well a person or an organization attain desired goal(s). E.g., a company might use "the number of new customers gained" as a metric to evaluate the success of a marketing campaign. The issue of metric fixation is said to arise if the decision maker(s) focus excessively on the metrics, often to the point that they treat "attaining desired values on the metrics" as a core goal (instead of simply an indicator of successes). For example, a school may want to improve the number of students who pass a certain test (metric = "number of students who pass"). This is based on the assumption that the said test truly can evaluate students' ability to succeed in the real world (assuming there already is a good definition of what "success" means). If the said test fails to evaluate the students' ability to function in the working world, focusing solely on increasing their scores on this test might cause the school to ignore other learning goals also crucial for real world functioning. As a result, the students' developments might be impaired.[1][2]

The concept of metric fixation was first mentioned in the 2018 book The Tyranny of Metrics.[3] Since then, it has drawn the attention of some management researchers and data scientists.[2][4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metric_fixation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Standards_and_measurement_stubs

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_reference_standard

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dry_gallon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bureau_of_Normalization

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_track

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calibration_gas

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emission_test_cycle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classification_of_Types_of_Construction

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atom_(time)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bite_force_quotient

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Day_of_Six_Billion

Population is the term typically used to refer to the number of people in a single area. Governments conduct a census to quantify the size of a resident population within a given jurisdiction. The term is also applied to animals, microorganisms, and plants, and has specific uses within such fields as ecology and genetics.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Population

Human overpopulation (or human population overshoot) is the hypothetical state in which human populations can become too large to be sustained by their environment or resources in the long term. The topic is usually discussed in the context of world population, though it may concern individual nations, regions, and cities.

Since 1804, the global human population has increased from 1 billion to 8 billion due to medical advancements and improved agricultural productivity. According to the most recent United Nations' projections, "[t]he global population is expected to reach 9.7 billion in 2050 and 10.4 billion in 2100 [assuming] a decline of fertility for countries where large families are still prevalent."[1] Those concerned by this trend argue that they result in levels of resource consumption and pollution which exceed the environment's carrying capacity, leading to population overshoot.[2] The population overshoot hypothesis is often discussed in relation to other population concerns such as population momentum, biodiversity loss,[3] hunger and malnutrition,[4] resource depletion, and the overall human impact on the environment.[5]

Early discussions of overpopulation in English were spurred by the work of Thomas Malthus. Discussions of overpopulation follow a similar line of inquiry as Malthusianism and its Malthusian catastrophe,[6][7] a hypothetical event where population exceeds agricultural capacity, causing famine or war over resources, resulting in poverty and depopulation. More recent discussion of overpopulation was popularized by Paul Ehrlich in his 1968 book The Population Bomb and subsequent writings.[8][9] Ehrlich described overpopulation as a function of overconsumption,[10] arguing that overpopulation should be defined by a population being unable to sustain itself without depleting non-renewable resources.[11][12][13]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_overpopulation

Population growth is the increase in the number of people in a population or dispersed group. Actual global human population growth amounts to around 83 million annually, or 1.1% per year.[2] The global population has grown from 1 billion in 1800 to 7.9 billion in 2020.[3] The UN projected population to keep growing, and estimates have put the total population at 8.6 billion by mid-2030, 9.8 billion by mid-2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100.[4] However, some academics outside the UN have increasingly developed human population models that account for additional downward pressures on population growth; in such a scenario population would peak before 2100.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Population_growth

Population projections are attempts to show how the human population statistics might change in the future.[1] These projections are an important input to forecasts of the population's impact on this planet and humanity's future well-being.[2] Models of population growth take trends in human development, and apply projections into the future.[3] These models use trend-based-assumptions about how populations will respond to economic, social and technological forces to understand how they will affect fertility and mortality, and thus population growth.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Projections_of_population_growth

The Journal of Computational and Nonlinear Dynamics is a quarterly peer-reviewed multidisciplinary scientific journal covering the study of nonlinear dynamics. It was established in 2006 and is published by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. The editor-in-chief is Balakumar Balachandran (University of Maryland). According to the Journal Citation Reports, the journal has a 2017 impact factor of 1.996.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journal_of_Computational_and_Nonlinear_Dynamics

Systems science is the field of science surrounding systems theory, cybernetics, and the science of complex systems. As an interdisciplinary science, it is applicable in a variety of areas, such as engineering, biology, medicine and social sciences.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Systems_science

In simple terms, risk is the possibility of something bad happening.[1] Risk involves uncertainty about the effects/implications of an activity with respect to something that humans value (such as health, well-being, wealth, property or the environment), often focusing on negative, undesirable consequences.[2] Many different definitions have been proposed. The international standard definition of risk for common understanding in different applications is “effect of uncertainty on objectives”.[3]

The understanding of risk, the methods of assessment and management, the descriptions of risk and even the definitions of risk differ in different practice areas (business, economics, environment, finance, information technology, health, insurance, safety, security etc). This article provides links to more detailed articles on these areas. The international standard for risk management, ISO 31000, provides principles and generic guidelines on managing risks faced by organizations.[4]

Definitions of risk

Oxford English Dictionary

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) cites the earliest use of the word in English (in the spelling of risque from its French original, 'risque') as of 1621, and the spelling as risk from 1655. While including several other definitions, the OED 3rd edition defines risk as:

(Exposure to) the possibility of loss, injury, or other adverse or welcome circumstance; a chance or situation involving such a possibility.[5]

The Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary gives a simple summary, defining risk as “the possibility of something bad happening”.[1]

International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Guide 73 provides basic vocabulary to develop common understanding on risk management concepts and terms across different applications. ISO Guide 73:2009 defines risk as:

effect of uncertainty on objectives

Note 1: An effect is a deviation from the expected – positive or negative.

Note 2: Objectives can have different aspects (such as financial, health and safety, and environmental goals) and can apply at different levels (such as strategic, organization-wide, project, product and process).

Note 3: Risk is often characterized by reference to potential events and consequences or a combination of these.

Note 4: Risk is often expressed in terms of a combination of the consequences of an event (including changes in circumstances) and the associated likelihood of occurrence.

Note 5: Uncertainty is the state, even partial, of deficiency of information related to, understanding or knowledge of, an event, its consequence, or likelihood.[3]

This definition was developed by an international committee representing over 30 countries and is based on the input of several thousand subject matter experts. It was first adopted in 2002. Its complexity reflects the difficulty of satisfying fields that use the term risk in different ways. Some restrict the term to negative impacts (“downside risks”), while others include positive impacts (“upside risks”).

ISO 31000:2018 “Risk management — Guidelines” uses the same definition with a simpler set of notes.[4]

Other

Many other definitions of risk have been influential:

- “Source of harm”. The earliest use of the word “risk” was as a synonym for the much older word “hazard”, meaning a potential source of harm. This definition comes from Blount’s “Glossographia” (1661)[6] and was the main definition in the OED 1st (1914) and 2nd (1989) editions. Modern equivalents refer to “unwanted events” [7] or “something bad that might happen”.[1]

- “Chance of harm”. This definition comes from Johnson’s “Dictionary of the English Language” (1755), and has been widely paraphrased, including “possibility of loss” [5] or “probability of unwanted events”.[7]

- “Uncertainty about loss”. This definition comes from Willett’s “Economic Theory of Risk and Insurance” (1901).[8] This links “risk” to “uncertainty”, which is a broader term than chance or probability.

- “Measurable uncertainty”. This definition comes from Knight’s “Risk, Uncertainty and Profit” (1921).[9] It allows “risk” to be used equally for positive and negative outcomes. In insurance, risk involves situations with unknown outcomes but known probability distributions.[10]

- “Volatility of return”. Equivalence between risk and variance of return was first identified in Markovitz’s “Portfolio Selection” (1952).[11] In finance, volatility of return is often equated to risk.[12]

- “Statistically expected loss”. The expected value of loss was used to define risk by Wald (1939) in what is now known as decision theory.[13] The probability of an event multiplied by its magnitude was proposed as a definition of risk for the planning of the Delta Works in 1953, a flood protection program in the Netherlands.[14] It was adopted by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (1975),[15] and remains widely used.[7]

- “Likelihood and severity of events”. The “triplet” definition of risk as “scenarios, probabilities and consequences” was proposed by Kaplan & Garrick (1981).[16] Many definitions refer to the likelihood/probability of events/effects/losses of different severity/consequence, e.g. ISO Guide 73 Note 4.[3]

- “Consequences and associated uncertainty”. This was proposed by Kaplan & Garrick (1981).[16] This definition is preferred in Bayesian analysis, which sees risk as the combination of events and uncertainties about them.[17]

- “Uncertain events affecting objectives”. This definition was adopted by the Association for Project Management (1997).[18][19] With slight rewording it became the definition in ISO Guide 73.[3]

- “Uncertainty of outcome”. This definition was adopted by the UK Cabinet Office (2002)[20] to encourage innovation to improve public services. It allowed “risk” to describe either “positive opportunity or negative threat of actions and events”.

- “Asset, threat and vulnerability”. This definition comes from the Threat Analysis Group (2010) in the context of computer security.[21]

- “Human interaction with uncertainty”. This definition comes from Cline (2015)[22] in the context of adventure education.

Some resolve these differences by arguing that the definition of risk is subjective. For example:

No definition is advanced as the correct one, because there is no one definition that is suitable for all problems. Rather, the choice of definition is a political one, expressing someone’s views regarding the importance of different adverse effects in a particular situation.[23]

The Society for Risk Analysis concludes that “experience has shown that to agree on one unified set of definitions is not realistic”. The solution is “to allow for different perspectives on fundamental concepts and make a distinction between overall qualitative definitions and their associated measurements.”[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk

Economic risk

Economics is concerned with the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services. Economic risk arises from uncertainty about economic outcomes. For example, economic risk may be the chance that macroeconomic conditions like exchange rates, government regulation, or political stability will affect an investment or a company’s prospects.[24]

In economics, as in finance, risk is often defined as quantifiable uncertainty about gains and losses.

Environmental risk

Environmental risk arises from environmental hazards or environmental issues.

In the environmental context, risk is defined as “The chance of harmful effects to human health or to ecological systems”.[25]

Environmental risk assessment aims to assess the effects of stressors, often chemicals, on the local environment.[26]

Financial risk

Finance is concerned with money management and acquiring funds.[27] Financial risk arises from uncertainty about financial returns. It includes market risk, credit risk, liquidity risk and operational risk.

In finance, risk is the possibility that the actual return on an investment will be different from its expected return.[28] This includes not only "downside risk" (returns below expectations, including the possibility of losing some or all of the original investment) but also "upside risk" (returns that exceed expectations). In Knight’s definition, risk is often defined as quantifiable uncertainty about gains and losses. This contrasts with Knightian uncertainty, which cannot be quantified.

Financial risk modeling determines the aggregate risk in a financial portfolio. Modern portfolio theory measures risk using the variance (or standard deviation) of asset prices. More recent risk measures include value at risk.

Because investors are generally risk averse, investments with greater inherent risk must promise higher expected returns.[29]

Financial risk management uses financial instruments to manage exposure to risk. It includes the use of a hedge to offset risks by adopting a position in an opposing market or investment.

In financial audit, audit risk refers to the potential that an audit report may fail to detect material misstatement either due to error or fraud.

Health risk

Health risks arise from disease and other biological hazards.

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution, patterns and determinants of health and disease. It is a cornerstone of public health, and shapes policy decisions by identifying risk factors for disease and targets for preventive healthcare.

In the context of public health, risk assessment is the process of characterizing the nature and likelihood of a harmful effect to individuals or populations from certain human activities. Health risk assessment can be mostly qualitative or can include statistical estimates of probabilities for specific populations.

A health risk assessment (also referred to as a health risk appraisal and health & well-being assessment) is a questionnaire screening tool, used to provide individuals with an evaluation of their health risks and quality of life

Health, safety, and environment risks

Health, safety, and environment (HSE) are separate practice areas; however, they are often linked. The reason is typically to do with organizational management structures; however, there are strong links among these disciplines. One of the strongest links is that a single risk event may have impacts in all three areas, albeit over differing timescales. For example, the uncontrolled release of radiation or a toxic chemical may have immediate short-term safety consequences, more protracted health impacts, and much longer-term environmental impacts. Events such as Chernobyl, for example, caused immediate deaths, and in the longer term, deaths from cancers, and left a lasting environmental impact leading to birth defects, impacts on wildlife, etc.

Information technology risk

Information technology (IT) is the use of computers to store, retrieve, transmit, and manipulate data. IT risk (or cyber risk) arises from the potential that a threat may exploit a vulnerability to breach security and cause harm. IT risk management applies risk management methods to IT to manage IT risks. Computer security is the protection of IT systems by managing IT risks.

Information security is the practice of protecting information by mitigating information risks. While IT risk is narrowly focused on computer security, information risks extend to other forms of information (paper, microfilm).

Occupational risk

Occupational health and safety is concerned with occupational hazards experienced in the workplace.

The Occupational Health and Safety Assessment Series (OHSAS) standard OHSAS 18001 in 1999 defined risk as the “combination of the likelihood and consequence(s) of a specified hazardous event occurring”. In 2018 this was replaced by ISO 45001 “Occupational health and safety management systems”, which use the ISO Guide 73 definition.

Project risk

A project is an individual or collaborative undertaking planned to achieve a specific aim. Project risk is defined as, "an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, has a positive or negative effect on a project’s objectives”. Project risk management aims to increase the likelihood and impact of positive events and decrease the likelihood and impact of negative events in the project.[32] [33]

Safety risk

Safety is concerned with a variety of hazards that may result in accidents causing harm to people, property and the environment. In the safety field, risk is typically defined as the “likelihood and severity of hazardous events”. Safety risks are controlled using techniques of risk management.

A high reliability organisation (HRO) involves complex operations in environments where catastrophic accidents could occur. Examples include aircraft carriers, air traffic control, aerospace and nuclear power stations. Some HROs manage risk in a highly quantified way. The technique is usually referred to as Probabilistic Risk Assessment (PRA). See WASH-1400 for an example of this approach. The incidence rate can also be reduced due to the provision of better occupational health and safety programmes [34]

Security risk

Security is freedom from, or resilience against, potential harm caused by others.

A security risk is "any event that could result in the compromise of organizational assets i.e. the unauthorized use, loss, damage, disclosure or modification of organizational assets for the profit, personal interest or political interests of individuals, groups or other entities."[35]

Security risk management involves protection of assets from harm caused by deliberate acts.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk

ISO 31000, the international standard for risk management,[4] describes a risk management process that consists of the following elements:

- Communicating and consulting

- Establishing the scope, context and criteria

- Risk assessment - recognising and characterising risks, and evaluating their significance to support decision-making. This includes risk identification, risk analysis and risk evaluation.

- Risk treatment - selecting and implementing options for addressing risk.

- Monitoring and reviewing

- Recording and reporting

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk

Psychology of risk

Risk perception

Intuitive risk assessment

An understanding that future events are uncertain and a particular concern about harmful ones may arise in anyone living in a community, experiencing seasons, hunting animals or growing crops. Most adults therefore have an intuitive understanding of risk. This may not be exclusive to humans.[47]

In ancient times, the dominant belief was in divinely determined fates, and attempts to influence the gods may be seen as early forms of risk management. Early uses of the word ‘risk’ coincided with an erosion of belief in divinely ordained fate.[48]

Risk perception is the subjective judgement that people make about the characteristics and severity of a risk. At its most basic, the perception of risk is an intuitive form of risk analysis.[49]

Heuristics and biases

Intuitive understanding of risk differs in systematic ways from accident statistics. When making judgements about uncertain events, people rely on a few heuristic principles, which convert the task of estimating probabilities to simpler judgements. These heuristics are useful but suffer from systematic biases.[50]

The “availability heuristic” is the process of judging the probability of an event by the ease with which instances come to mind. In general, rare but dramatic causes of death are over-estimated while common unspectacular causes are under-estimated.[51]

An “availability cascade” is a self-reinforcing cycle in which public concern about relatively minor events is amplified by media coverage until the issue becomes politically important.[52]

Despite the difficulty of thinking statistically, people are typically over-confident in their judgements. They over-estimate their understanding of the world and under-estimate the role of chance.[53] Even experts are over-confident in their judgements.[54]

Psychometric paradigm

The “psychometric paradigm” assumes that risk is subjectively defined by individuals, influenced by factors that can be elicited by surveys.[55] People’s perception of the risk from different hazards depends on three groups of factors:

- Dread – the degree to which the hazard is feared or might be fatal, catastrophic, uncontrollable, inequitable, involuntary, increasing or difficult to reduce.

- Unknown - the degree to which the hazard is unknown to those exposed, unobservable, delayed, novel or unknown to science.

- Number of people exposed.

Hazards with high perceived risk are in general seen as less acceptable and more in need of reduction.[56]

Cultural theory of risk

Cultural Theory views risk perception as a collective phenomenon by which different cultures select some risks for attention and ignore others, with the aim of maintaining their particular way of life.[57] Hence risk perception varies according to the preoccupations of the culture. The theory distinguishes variations known as “group” (the degree of binding to social groups) and “grid” (the degree of social regulation), leading to four world-views:[58]

- Hierarchists (high group /high grid), who tend to approve of technology providing its risks are evaluated as acceptable by experts.

- Egalitarians (high group/low grid), who tend to object to technology because it perpetuates inequalities that harm society and the environment.

- Individualists (low group/low grid), who tend to approve of technology and see risks as opportunities.

- Fatalists (low group/high grid), who do not knowingly take risks but tend to accept risks that are imposed on them

Cultural Theory helps explain why it can be difficult for people with different world-views to agree about whether a hazard is acceptable, and why risk assessments may be more persuasive for some people (e.g. hierarchists) than others. However, there is little quantitative evidence that shows cultural biases are strongly predictive of risk perception.[59]

Risk and emotion

The importance of emotion in risk

While risk assessment is often described as a logical, cognitive process, emotion also has a significant role in determining how people react to risks and make decisions about them.[60] Some argue that intuitive emotional reactions are the predominant method by which humans evaluate risk. A purely statistical approach to disasters lacks emotion and thus fails to convey the true meaning of disasters and fails to motivate proper action to prevent them.[61] This is consistent with psychometric research showing the importance of “dread” (an emotion) alongside more logical factors such as the number of people exposed.

The field of behavioural economics studies human risk-aversion, asymmetric regret, and other ways that human financial behaviour varies from what analysts call "rational". Recognizing and respecting the irrational influences on human decision making may improve naive risk assessments that presume rationality but in fact merely fuse many shared biases.

The affect heuristic

The “affect heuristic” proposes that judgements and decision-making about risks are guided, either consciously or unconsciously, by the positive and negative feelings associated with them. [62] This can explain why judgements about risks are often inversely correlated with judgements about benefits. Logically, risk and benefit are distinct entities, but it seems that both are linked to an individual’s feeling about a hazard.[63]

Fear, anxiety and risk

Worry or anxiety is an emotional state that is stimulated by anticipation of a future negative outcome, or by uncertainty about future outcomes. It is therefore an obvious accompaniment to risk, and is initiated by many hazards and linked to increases in perceived risk. It may be a natural incentive for risk reduction. However, worry sometimes triggers behaviour that is irrelevant or even increases objective measurements of risk.[64]

Fear is a more intense emotional response to danger, which increases the perceived risk. Unlike anxiety, it appears to dampen efforts at risk minimisation, possibly because it provokes a feeling of helplessness.[65]

Dread risk

It is common for people to dread some risks but not others: They tend to be very afraid of epidemic diseases, nuclear power plant failures, and plane accidents but are relatively unconcerned about some highly frequent and deadly events, such as traffic crashes, household accidents, and medical errors. One key distinction of dreadful risks seems to be their potential for catastrophic consequences,[66] threatening to kill a large number of people within a short period of time.[67] For example, immediately after the 11 September attacks, many Americans were afraid to fly and took their car instead, a decision that led to a significant increase in the number of fatal crashes in the time period following the 9/11 event compared with the same time period before the attacks.[68][69]

Different hypotheses have been proposed to explain why people fear dread risks. First, the psychometric paradigm suggests that high lack of control, high catastrophic potential, and severe consequences account for the increased risk perception and anxiety associated with dread risks. Second, because people estimate the frequency of a risk by recalling instances of its occurrence from their social circle or the media, they may overvalue relatively rare but dramatic risks because of their overpresence and undervalue frequent, less dramatic risks.[69] Third, according to the preparedness hypothesis, people are prone to fear events that have been particularly threatening to survival in human evolutionary history.[70] Given that in most of human evolutionary history people lived in relatively small groups, rarely exceeding 100 people,[71] a dread risk, which kills many people at once, could potentially wipe out one's whole group. Indeed, research found[72] that people's fear peaks for risks killing around 100 people but does not increase if larger groups are killed. Fourth, fearing dread risks can be an ecologically rational strategy.[73] Besides killing a large number of people at a single point in time, dread risks reduce the number of children and young adults who would have potentially produced offspring. Accordingly, people are more concerned about risks killing younger, and hence more fertile, groups.[74]

Outrage

Outrage is a strong moral emotion, involving anger over an adverse event coupled with an attribution of blame towards someone perceived to have failed to do what they should have done to prevent it. Outrage is the consequence of an event, involving a strong belief that risk management has been inadequate. Looking forward, it may greatly increase the perceived risk from a hazard.[75]

Human factors

One of the growing areas of focus in risk management is the field of human factors where behavioural and organizational psychology underpin our understanding of risk based decision making. This field considers questions such as "how do we make risk based decisions?", "why are we irrationally more scared of sharks and terrorists than we are of motor vehicles and medications?"

In decision theory, regret (and anticipation of regret) can play a significant part in decision-making, distinct from risk aversion[76][77](preferring the status quo in case one becomes worse off).

Framing[78] is a fundamental problem with all forms of risk assessment. In particular, because of bounded rationality (our brains get overloaded, so we take mental shortcuts), the risk of extreme events is discounted because the probability is too low to evaluate intuitively. As an example, one of the leading causes of death is road accidents caused by drunk driving – partly because any given driver frames the problem by largely or totally ignoring the risk of a serious or fatal accident.

For instance, an extremely disturbing event (an attack by hijacking, or moral hazards) may be ignored in analysis despite the fact it has occurred and has a nonzero probability. Or, an event that everyone agrees is inevitable may be ruled out of analysis due to greed or an unwillingness to admit that it is believed to be inevitable. These human tendencies for error and wishful thinking often affect even the most rigorous applications of the scientific method and are a major concern of the philosophy of science.

All decision-making under uncertainty must consider cognitive bias, cultural bias, and notational bias: No group of people assessing risk is immune to "groupthink": acceptance of obviously wrong answers simply because it is socially painful to disagree, where there are conflicts of interest.

Framing involves other information that affects the outcome of a risky decision. The right prefrontal cortex has been shown to take a more global perspective[79] while greater left prefrontal activity relates to local or focal processing.[80]

From the Theory of Leaky Modules[81] McElroy and Seta proposed that they could predictably alter the framing effect by the selective manipulation of regional prefrontal activity with finger tapping or monaural listening.[82] The result was as expected. Rightward tapping or listening had the effect of narrowing attention such that the frame was ignored. This is a practical way of manipulating regional cortical activation to affect risky decisions, especially because directed tapping or listening is easily done.

Psychology of risk taking

A growing area of research has been to examine various psychological aspects of risk taking. Researchers typically run randomised experiments with a treatment and control group to ascertain the effect of different psychological factors that may be associated with risk taking.[83] Thus, positive and negative feedback about past risk taking can affect future risk taking. In an experiment, people who were led to believe they are very competent at decision making saw more opportunities in a risky choice and took more risks, while those led to believe they were not very competent saw more threats and took fewer risks.[84]

Other considerations

Risk and uncertainty

In his seminal work Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit, Frank Knight (1921) established the distinction between risk and uncertainty.

... Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically distinct from the familiar notion of Risk, from which it has never been properly separated. The term "risk," as loosely used in everyday speech and in economic discussion, really covers two things which, functionally at least, in their causal relations to the phenomena of economic organization, are categorically different. ... The essential fact is that "risk" means in some cases a quantity susceptible of measurement, while at other times it is something distinctly not of this character; and there are far-reaching and crucial differences in the bearings of the phenomenon depending on which of the two is really present and operating. ... It will appear that a measurable uncertainty, or "risk" proper, as we shall use the term, is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all. We ... accordingly restrict the term "uncertainty" to cases of the non-quantitive type.:[85]

Thus, Knightian uncertainty is immeasurable, not possible to calculate, while in the Knightian sense risk is measurable.

Another distinction between risk and uncertainty is proposed by Douglas Hubbard:[86][12]

- Uncertainty: The lack of complete certainty, that is, the existence of more than one possibility. The "true" outcome/state/result/value is not known.

- Measurement of uncertainty: A set of probabilities assigned to a set of possibilities. Example: "There is a 60% chance this market will double in five years"

- Risk: A state of uncertainty where some of the possibilities involve a loss, catastrophe, or other undesirable outcome.

- Measurement of risk: A set of possibilities each with quantified probabilities and quantified losses. Example: "There is a 40% chance the proposed oil well will be dry with a loss of $12 million in exploratory drilling costs".

In this sense, one may have uncertainty without risk but not risk without uncertainty. We can be uncertain about the winner of a contest, but unless we have some personal stake in it, we have no risk. If we bet money on the outcome of the contest, then we have a risk. In both cases there are more than one outcome. The measure of uncertainty refers only to the probabilities assigned to outcomes, while the measure of risk requires both probabilities for outcomes and losses quantified for outcomes.

Mild Versus Wild Risk

Benoit Mandelbrot distinguished between "mild" and "wild" risk and argued that risk assessment and analysis must be fundamentally different for the two types of risk.[87] Mild risk follows normal or near-normal probability distributions, is subject to regression to the mean and the law of large numbers, and is therefore relatively predictable. Wild risk follows fat-tailed distributions, e.g., Pareto or power-law distributions, is subject to regression to the tail (infinite mean or variance, rendering the law of large numbers invalid or ineffective), and is therefore difficult or impossible to predict. A common error in risk assessment and analysis is to underestimate the wildness of risk, assuming risk to be mild when in fact it is wild, which must be avoided if risk assessment and analysis are to be valid and reliable, according to Mandelbrot.

Risk attitude, appetite and tolerance

The terms risk attitude, appetite, and tolerance are often used similarly to describe an organisation's or individual's attitude towards risk-taking. One's attitude may be described as risk-averse, risk-neutral, or risk-seeking. Risk tolerance looks at acceptable/unacceptable deviations from what is expected.[clarification needed] Risk appetite looks at how much risk one is willing to accept. There can still be deviations that are within a risk appetite. For example, recent research finds that insured individuals are significantly likely to divest from risky asset holdings in response to a decline in health, controlling for variables such as income, age, and out-of-pocket medical expenses.[88]

Gambling is a risk-increasing investment, wherein money on hand is risked for a possible large return, but with the possibility of losing it all. Purchasing a lottery ticket is a very risky investment with a high chance of no return and a small chance of a very high return. In contrast, putting money in a bank at a defined rate of interest is a risk-averse action that gives a guaranteed return of a small gain and precludes other investments with possibly higher gain. The possibility of getting no return on an investment is also known as the rate of ruin.

Risk compensation is a theory which suggests that people typically adjust their behavior in response to the perceived level of risk, becoming more careful where they sense greater risk and less careful if they feel more protected.[89] By way of example, it has been observed that motorists drove faster when wearing seatbelts and closer to the vehicle in front when the vehicles were fitted with anti-lock brakes.

Risk and autonomy

The experience of many people who rely on human services for support is that 'risk' is often used as a reason to prevent them from gaining further independence or fully accessing the community, and that these services are often unnecessarily risk averse.[90] "People's autonomy used to be compromised by institution walls, now it's too often our risk management practices", according to John O'Brien.[91] Michael Fischer and Ewan Ferlie (2013) find that contradictions between formal risk controls and the role of subjective factors in human services (such as the role of emotions and ideology) can undermine service values, so producing tensions and even intractable and 'heated' conflict.[92]

Risk society

Anthony Giddens and Ulrich Beck argued that whilst humans have always been subjected to a level of risk – such as natural disasters – these have usually been perceived as produced by non-human forces. Modern societies, however, are exposed to risks such as pollution, that are the result of the modernization process itself. Giddens defines these two types of risks as external risks and manufactured risks. The term Risk society was coined in the 1980s and its popularity during the 1990s was both as a consequence of its links to trends in thinking about wider modernity, and also to its links to popular discourse, in particular the growing environmental concerns during the period.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk#Psychology_of_risk

Risk management is the identification, evaluation, and prioritization of risks (defined in ISO 31000 as the effect of uncertainty on objectives) followed by coordinated and economical application of resources to minimize, monitor, and control the probability or impact of unfortunate events[1] or to maximize the realization of opportunities.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_management

Fear, anxiety and risk

Worry or anxiety is an emotional state that is stimulated by anticipation of a future negative outcome, or by uncertainty about future outcomes. It is therefore an obvious accompaniment to risk, and is initiated by many hazards and linked to increases in perceived risk. It may be a natural incentive for risk reduction. However, worry sometimes triggers behaviour that is irrelevant or even increases objective measurements of risk.[64]

Fear is a more intense emotional response to danger, which increases the perceived risk. Unlike anxiety, it appears to dampen efforts at risk minimisation, possibly because it provokes a feeling of helplessness.[65]

Dread risk

It is common for people to dread some risks but not others: They tend to be very afraid of epidemic diseases, nuclear power plant failures, and plane accidents but are relatively unconcerned about some highly frequent and deadly events, such as traffic crashes, household accidents, and medical errors. One key distinction of dreadful risks seems to be their potential for catastrophic consequences,[66] threatening to kill a large number of people within a short period of time.[67] For example, immediately after the 11 September attacks, many Americans were afraid to fly and took their car instead, a decision that led to a significant increase in the number of fatal crashes in the time period following the 9/11 event compared with the same time period before the attacks.[68][69]

Different hypotheses have been proposed to explain why people fear dread risks. First, the psychometric paradigm suggests that high lack of control, high catastrophic potential, and severe consequences account for the increased risk perception and anxiety associated with dread risks. Second, because people estimate the frequency of a risk by recalling instances of its occurrence from their social circle or the media, they may overvalue relatively rare but dramatic risks because of their overpresence and undervalue frequent, less dramatic risks.[69] Third, according to the preparedness hypothesis, people are prone to fear events that have been particularly threatening to survival in human evolutionary history.[70] Given that in most of human evolutionary history people lived in relatively small groups, rarely exceeding 100 people,[71] a dread risk, which kills many people at once, could potentially wipe out one's whole group. Indeed, research found[72] that people's fear peaks for risks killing around 100 people but does not increase if larger groups are killed. Fourth, fearing dread risks can be an ecologically rational strategy.[73] Besides killing a large number of people at a single point in time, dread risks reduce the number of children and young adults who would have potentially produced offspring. Accordingly, people are more concerned about risks killing younger, and hence more fertile, groups.[74]

Outrage

Outrage is a strong moral emotion, involving anger over an adverse event coupled with an attribution of blame towards someone perceived to have failed to do what they should have done to prevent it. Outrage is the consequence of an event, involving a strong belief that risk management has been inadequate. Looking forward, it may greatly increase the perceived risk from a hazard.[75]

Human factors

One of the growing areas of focus in risk management is the field of human factors where behavioural and organizational psychology underpin our understanding of risk based decision making. This field considers questions such as "how do we make risk based decisions?", "why are we irrationally more scared of sharks and terrorists than we are of motor vehicles and medications?"

In decision theory, regret (and anticipation of regret) can play a significant part in decision-making, distinct from risk aversion[76][77](preferring the status quo in case one becomes worse off).

Framing[78] is a fundamental problem with all forms of risk assessment. In particular, because of bounded rationality (our brains get overloaded, so we take mental shortcuts), the risk of extreme events is discounted because the probability is too low to evaluate intuitively. As an example, one of the leading causes of death is road accidents caused by drunk driving – partly because any given driver frames the problem by largely or totally ignoring the risk of a serious or fatal accident.

For instance, an extremely disturbing event (an attack by hijacking, or moral hazards) may be ignored in analysis despite the fact it has occurred and has a nonzero probability. Or, an event that everyone agrees is inevitable may be ruled out of analysis due to greed or an unwillingness to admit that it is believed to be inevitable. These human tendencies for error and wishful thinking often affect even the most rigorous applications of the scientific method and are a major concern of the philosophy of science.

All decision-making under uncertainty must consider cognitive bias, cultural bias, and notational bias: No group of people assessing risk is immune to "groupthink": acceptance of obviously wrong answers simply because it is socially painful to disagree, where there are conflicts of interest.

Framing involves other information that affects the outcome of a risky decision. The right prefrontal cortex has been shown to take a more global perspective[79] while greater left prefrontal activity relates to local or focal processing.[80]

From the Theory of Leaky Modules[81] McElroy and Seta proposed that they could predictably alter the framing effect by the selective manipulation of regional prefrontal activity with finger tapping or monaural listening.[82] The result was as expected. Rightward tapping or listening had the effect of narrowing attention such that the frame was ignored. This is a practical way of manipulating regional cortical activation to affect risky decisions, especially because directed tapping or listening is easily done.

Psychology of risk taking

A growing area of research has been to examine various psychological aspects of risk taking. Researchers typically run randomised experiments with a treatment and control group to ascertain the effect of different psychological factors that may be associated with risk taking.[83] Thus, positive and negative feedback about past risk taking can affect future risk taking. In an experiment, people who were led to believe they are very competent at decision making saw more opportunities in a risky choice and took more risks, while those led to believe they were not very competent saw more threats and took fewer risks.[84]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambiguity_aversion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/External_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Event_chain_methodology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_catastrophic_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazard

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Record_linkage#Entity_resolution

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inherent_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inherent_risk_(accounting)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legal_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Safety-critical_system

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liquidity_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moral_hazard

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operational_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Probabilistic_risk_assessment

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reliability_engineering

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_compensation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk-neutral_measure

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_perception

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sampling_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Systemic_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Systematic_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncertainty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vulnerability

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absolute_probability_judgement

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiple-criteria_decision_analysis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_metric

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_register

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_matrix

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Probability_density_function

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expected_utility_hypothesis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Value_at_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expected_value

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loss_function#Expected_loss

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decision_rule

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loss_function

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_neutral

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volatility_(finance)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Variance

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk#Risk_evaluation_and_risk_criteria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Availability_cascade

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affect_heuristic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Experimental_psychology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Experimental_psychology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Debriefing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Missing_letter_effect

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudoscope

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudoword

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repetition_priming

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sensory_overload

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stimulus_onset_asynchrony

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_Deadly_Initials

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tunnel_effect

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pair_by_association

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pavlov%27s_typology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perceptual_attack_time

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generality_(psychology)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effort_heuristic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Experimental_analysis_of_behavior

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Experimental_pragmatics

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/External_inhibition

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eyeblink_conditioning

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neutral_stimulus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heuristic_(psychology)

The curse of knowledge is a cognitive bias that occurs when an individual, who is communicating with other individuals, assumes that other individuals have similar background and depth of knowledge to understand.[1] This bias is also called by some authors the curse of expertise.[2]

For example, in a classroom setting, teachers may have difficulty if they cannot put themselves in the position of the student. A knowledgeable professor might no longer remember the difficulties that a young student encounters when learning a new subject for the first time. This curse of knowledge also explains the danger behind thinking about student learning based on what appears best to faculty members, as opposed to what has been verified with students.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curse_of_knowledge

In contract theory and economics, information asymmetry deals with the study of decisions in transactions where one party has more or better information than the other.

Information asymmetry creates an imbalance of power in transactions, which can sometimes cause the transactions to be inefficient, causing market failure in the worst case. Examples of this problem are adverse selection,[1] moral hazard, [2] and monopolies of knowledge.[3]

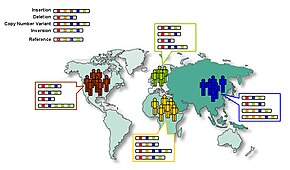

A common way to visualise information asymmetry is with a scale, with one side being the seller and the other the buyer. When the seller has more or better information, the transaction will more likely occur in the seller's favour ("the balance of power has shifted to the seller"). An example of this could be when a used car is sold, the seller is likely to have a much better understanding of the car's condition and hence its market value than the buyer, who can only estimate the market value based on the information provided by the seller and their own assessment of the vehicle.[4] The balance of power can, however, also be in the hands of the buyer. When buying health insurance, the buyer is not always required to provide full details of future health risks. By not providing this information to the insurance company, the buyer will pay the same premium as someone much less likely to require a payout in the future.[5] The adjacent image illustrates the balance of power between two agents when there is Perfect information. Perfect information means that all parties have complete knowledge. If the buyer has more information, the power to manipulate the transaction will be represented by the scale leaning towards the buyer's side.

Information asymmetry extends to non-economic behaviour. Private firms have better information than regulators about the actions that they would take in the absence of regulation, and the effectiveness of a regulation may be undermined.[6] International relations theory has recognized that wars may be caused by asymmetric information[7] and that "Most of the great wars of the modern era resulted from leaders miscalculating their prospects for victory".[8] Jackson and Morelli wrote that there is asymmetric information between national leaders, when there are differences "in what they know [i.e. believe] about each other's armaments, quality of military personnel and tactics, determination, geography, political climate, or even just about the relative probability of different outcomes" or where they have "incomplete information about the motivations of other agents".[9]